Treason of Intellectuals

In the Western world, public trust in intellectuals is perhaps lower than ever—and the intellectuals themselves are largely to blame..

If interested in AI, check my other page where I write on prospects for LLM tutors.

Please also subscribe to make sure you will not miss future posts. Subscription is free. Your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

-+-+-+-+

Most Turkish intellectuals are convinced that they—and only they—know what’s best for the nation. If the populace disagrees, it must be because they are ignorant. These intellectuals see their role as that of enlightened guides. In fact, the Turkish word for intellectual is “aydın”, which literally means “the enlightened one.”

This intellectual snobbery is not unique to Turkey. It is increasingly a global phenomenon. Intellectuals in countries as diverse as Hungary, Brazil, Israel, and even the United States blame “ignorant” electorates for electing populist strongmen and creating national crises. These strongmen often centralize power, undermine key institutions, and erode democratic norms. But rather than reflect on why such leaders appeal to so many, intellectuals often double down on their disdain for the public.

This condescension isn’t confined to politically active intellectuals. Take any controversial topic—climate change, vaccines, ivermectin—and you’ll find a familiar pattern: intellectuals blaming the public for failing to “accept the science.” It was this very attitude that prompted me to write this post, after watching a Robinson Erhardt interview with philosopher Massimo Pigliucci.

Around the 43-minute mark, Pigliucci recounts the story of a relative who, during the pandemic, asked him to send some scientific papers about COVID vaccines. Here’s what he said:

“I had a relative who, during the pandemic, asked me to send her some papers from the primary literature—about vaccines, COVID, and so on.

I asked her, ‘Why do you need them?’

She said, ‘I want to look for myself.’

I replied, ‘But you’re not a virologist or an epidemiologist. How are you going to look?’

Her answer was, ‘Well, I took one course in statistics in college.’

Oh, okay—if that’s all it takes to be an expert on vaccines, then knock yourself out…”

And later:

“What I find very funny is if you suggested someone do their own research on some esoteric branch of math—like motivic cohomology—they’d say, ‘No way, I’m not capable of that.’”

Pigliucci’s tone is unmistakably condescending. He ridicules the idea of “doing your own research” as if it were a foolish act of arrogance. What disappointed me was that the host never asked the obvious follow-up question: Why are so many ordinary people compelled to do their own research in the first place, instead of trusting expert opinion?

I can only speak for myself. By the end of the first year of the pandemic, I had lost confidence in the authorities. There were many reasons for this, but the most important was their suppression of dissenting medical voices. Doctors and scientists who expressed alternative views—however reasoned or evidence-based—were silenced, punished, or publicly shamed. This made me wonder: What are they hiding? And so I began seeking out independent, credible sources of information.

In hindsight, I understand why people began distrusting expert opinion. The public has good reason not to accept the scientific narrative at face value.

He Who Pays the Piper Calls the Tune

Scientific research doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It requires money—lots of it—for equipment, skilled personnel, and institutional support. And in many fields with commercial relevance, that money often comes from the private sector.

There is nothing inherently wrong with companies funding research. Researchers can—and often should—collaborate with industry. But problems arise when researchers start identifying with their funders and become their public advocates. This doesn’t always involve lying or fabricating data. Rather, it creates a subtle but powerful bias: researchers avoid questions that might harm their sponsors’ interests and gravitate toward projects that will do otherwise.

Academics are incentivized to attract funding. In universities, one key performance metric is how much external funding a researcher brings in. In non-university research institutions, the situation can be even more intense.

I worked at CSIRO about 30 years ago. At the time, the organization was required to secure external funding equal to roughly 50% of its government grant—about 35% of its total budget. Since administrative and executive staff rarely generate income directly, the pressure fell heavily on research teams. The result: even under the best conditions, researchers focused on projects with commercial potential, while avoiding areas that could challenge or harm corporate interests.

This is a systemic issue, and I don’t claim to have a solution. Industry collaboration can be a good thing. It connects academics to real-world problems, gives students exposure to industry, and keeps research grounded in practical relevance.

But we must also acknowledge the downside: the growing public perception that academics have become mouthpieces rather than truth-seekers. That perception, I believe, is at the heart of the public’s declining trust in the scientific establishment.

Breaking the Truth to Serve an Alternative Tune

There is another group of intellectuals who have inadvertently contributed to the erosion of public trust—this time, not through elitism, but through overzealousness in the name of a good cause. Unlike the first group, these individuals are not confined to universities or research institutions. They may come from all walks of life. Many are motivated by a genuine desire to serve the public good.

However, their strong belief in both themselves and their cause sometimes leads them to bend the truth in order to better illustrate a point. When accusing a company or an industry, they may cite evidence that is dubious or even false. If this is pointed out, they often deflect the criticism with lines like, “The specific example may not be accurate, but what I’m saying is still true—because if they haven’t done this, they would have if given the chance.”

These intellectuals see their role not just as truth-tellers, but as exposers of hidden lies—particularly those told by governments or corporations. Since direct evidence of such wrongdoing is often concealed or obfuscated, these well-meaning but frustrated critics may resort to exaggeration, or even invention. They justify this on the grounds that the wrongdoing surely exists—it just hasn’t been uncovered yet.

While the impact of this second group on public trust in science and intellectual discourse may be smaller than that of institutional elites, their willingness to dissemble is eagerly seized upon by their opponents. It fuels a cynical narrative: “Everyone lies. The truth is relative. You can’t believe anything.” This relativism doesn’t just undermine intellectual authority—it actively enables the continuation of the very wrongs these individuals seek to expose.

Final Thoughts

If intellectuals want to regain the trust of the public, they must begin by mending their attitudes and assumptions. We must find ways to collaborate with industry without compromising our ability to call things as they are. I know this is difficult, but full transparency in all research results should be the starting point—even when some of those results may be embarrassing for the sponsoring companies.

At the same time, we need to understand that “truth” is not something to be imposed from above, nor defended through elitism or noble deception. The moment intellectuals see themselves as a class apart—entitled to steer the public rather than serve it—they forfeit the very credibility they need to effect change. Rebuilding trust will not come from doubling down on condescension or moral certainty, but from rediscovering the intellectual virtues of doubt, transparency, accountability, and humility.

-+-+-+-+

Short Takes

Elections in Turkey in early 2026?

In May 2025, I wrote that “Turkey’s strategic interest lies in reconciliation with Syrian Kurds. But this is impossible without first resolving domestic conflicts with the PKK. This necessity motivated the fiercely nationalistic Bahçeli to issue, unsolicited, a call for peace negotiations last October.” This path required Turkey not favouring the Damascus HTŞ government against the Kurds in north-eastern Syria.

It looks like President Erdogan is reluctant to follow this path, probably because he favours the Islamist HTŞ government as the undisputed ruler in Syria. What Erdogan wants is however in conflict with the Syrian strategy adopted by the Hegemony1 and articulated by Bahceli. Erdogan no longer has the power to challenge the Hegemony. Therefore, if he persists in not following the script, I predict Bahceli join the opposition in calling for elections.

University graduates cannot find jobs

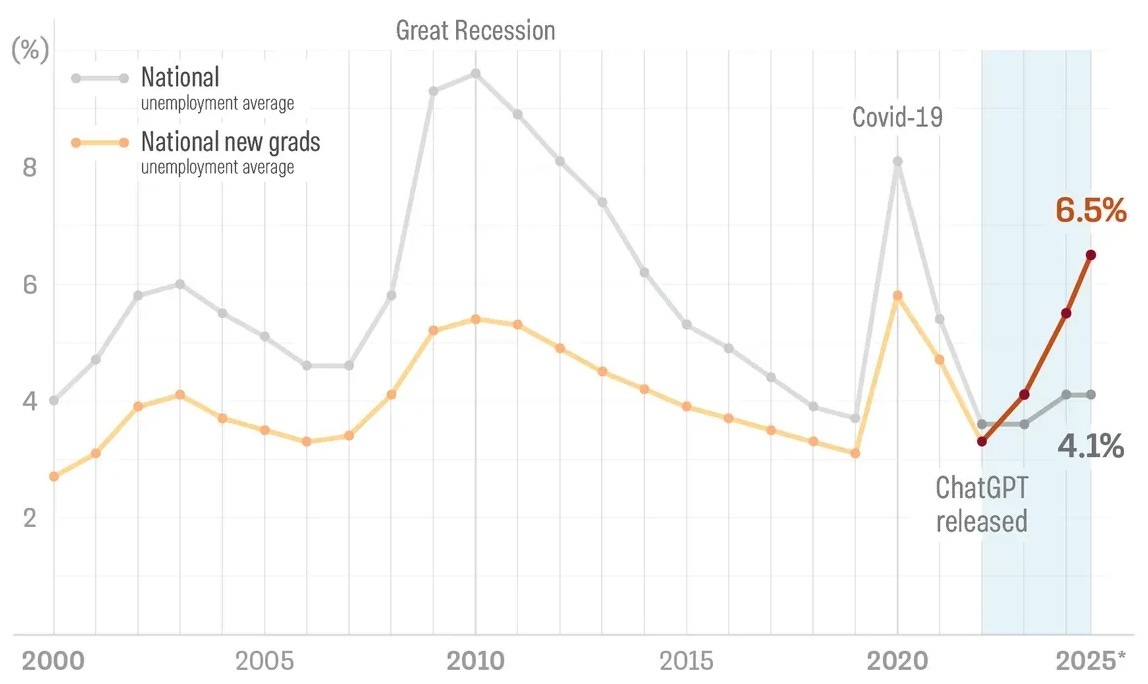

In USA, everyone is having it hard lately but recent college graduates find it the hardest. The following graph from GZERO Media shows the unemployment rate amongst the recent university graduates rising sharply since the introduction of ChatGPT. It is rising much faster than the national average also shown on the same graph.

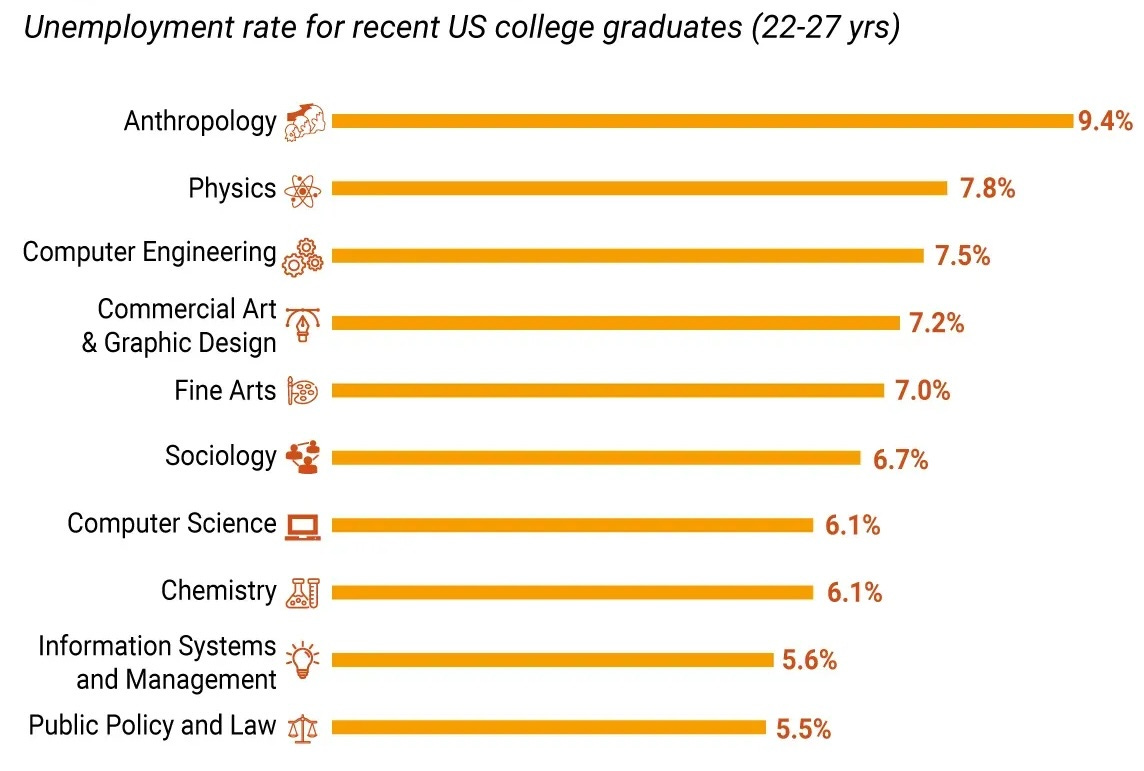

Correlation does not necessarily mean but cause and effect but when we look at the list of the disciplines where it is hardest to find jobs, it is difficult not to conclude that “AI” is the culprit:

I suppose anthropology graduates had always it found it difficult to find jobs but we are not used to seeing the disciplines of Physics (in this list probably because most physics graduates used to find employment in IT), computer engineering, computer science, information systems amongst the least employable professions. Mechanical Engineering seems to be safe at the moment.

Read two earlier posts this year on future prospects for university graduates and the universities.

Old people need to chew their food more carefully

Older adults are more likely to choke than children. In USA, 4,000-5,000 people choke to death every year and the great majority of them are over 65. The number of choking deaths is less than 200 for children. Aging muscles are responsible. I started chewing gum to strengthen my jaw muscles. I should be safe unless I choke on my chewing gum.

-+-+-+-+

Comparing Istanbul and Brisbane prices - AT index

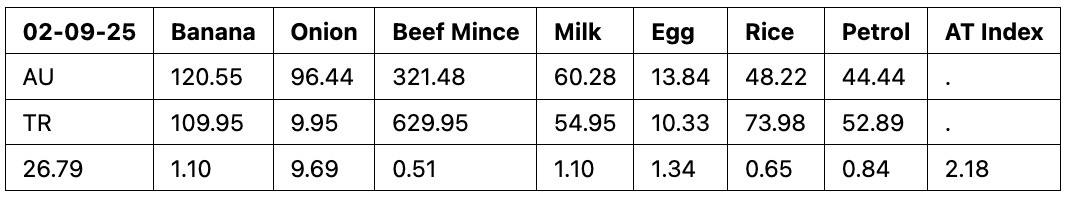

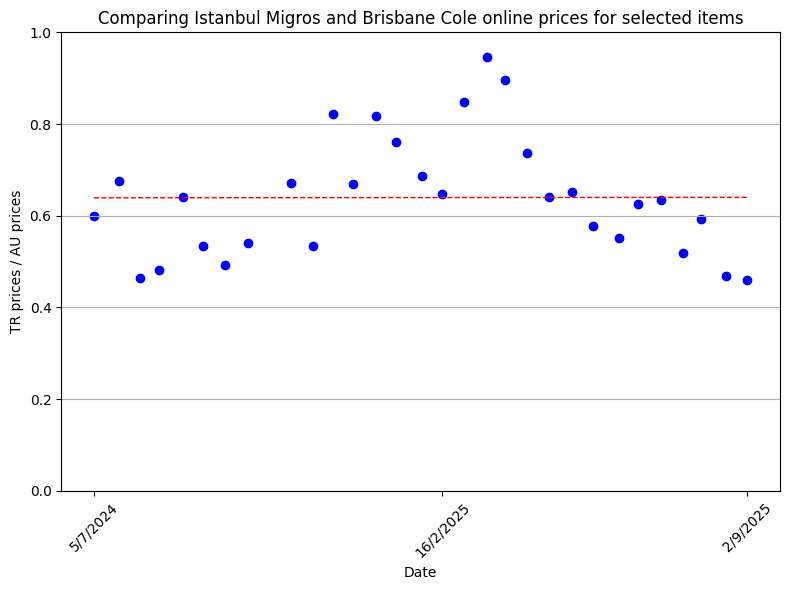

Based on my basket of goods, Turkish prices are about 65% of the Australian prices. Both Coles (AU) and Migros (TR) prices are expressed in Turkish liras for the items in the basket on 2 September 2025. I converted Coles prices to Turkish liras at the exchange rate of 1AUD=26.79TRY.

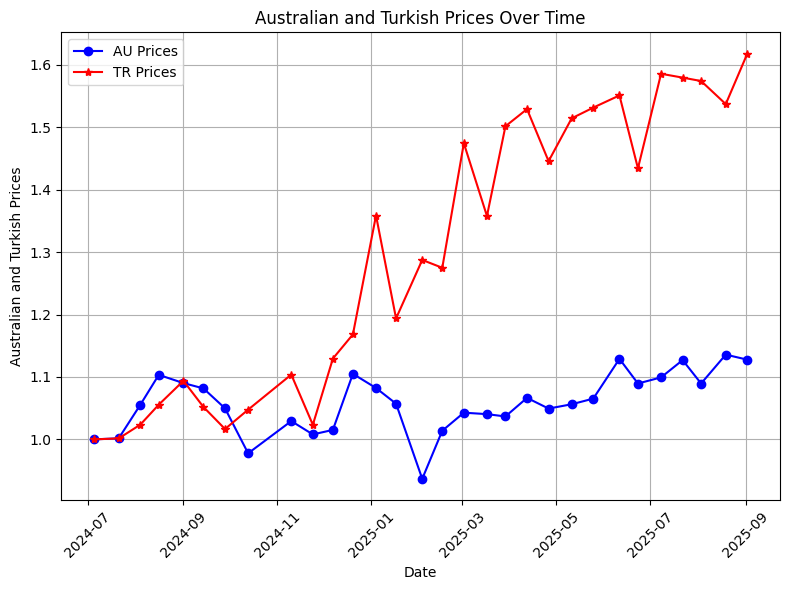

I started this graph on 5 July 2024. The Turkish prices were initially rising faster than the Australian prices. The trend reversed in February 2025. Since then, the Turkish prices have been getting increasingly lower than the Australian prices.

Nevertheless, some items, e.g. beef mince and rice, have consistently been more expensive in Istanbul. You do not see the individual items in these aggregate charts but they are listed in the raw data I have on github.

The following chart shows the variation of the total cost for the basket in each country separately taking 5 July 2024 as the base.

Wages

The Australian minimum wage was increased to almost $25/h on 3 June 2025. This corresponds to A$4000/month for a 160-hour month. The Australian workers being paid the minimum wage are about 2.6 million or about 18% of the total Australian work force.

The minimum wage in Turkey is 26,000 TRY/month. At the current exchange rate this corresponds to A$1018/month.

The code to create the above tables and the charts is in my github repository and can be downloaded if you are interested.

I decided to use the word Hegemony instead of the Elite Consensus. I use Hegemony in the Gramscian sense.