The End of the Erdoğan Era

The longest continuous rule in the history of the Turkish Republic is ending. What’s next for Turkey?

If you like what you read, copy and share the link, post it on another platform.

Please also subscribe to make sure you will not miss future posts. Subscription is free. Your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

-+-+-+-+

Turkey is near a critical juncture. The dominant force since 2001, the Erdoğan government, is facing a decline in popularity. The reason may be that, after years of remarkable growth, the Turkish economy is now struggling with severe instability, notably characterized by a dramatic currency decline over the past five years.

Interestingly, amidst this turmoil, the government has resumed peace negotiations with the PKK, aiming to resolve a conflict that dates back to the 1980s. Some interpret the move as President Erdoğan's strategy to expand his eroding support base and secure Kurdish support for constitutional changes necessary for his re-election. This is not my interpretation. I believe he is following broader consensus among Turkish elites about the country’s positioning in a newly multipolar world and peace with Kurds is an essential part of this. Of course, if there is an electoral advantage, Erdogan would try to use it but I do not think there is one and, even then, this is not the reason he is supporting the process. In fact, up until recently, he seemed to be reluctantly tolerating it rather than supporting it.

I anticipated much of this scenario over a year ago. I copy my April 2024 analysis:

The Revisionist period is now at an end. The new ordering of the elites is complete and there is a new consensus. I think the following are the parameters of this new consensus:

Turkey will maintain its Western identity but will develop independent regional and global policies

Turkey anticipates US leaving Middle East. This will create a vacuum in regional power dynamics. With Russia weakened after a Pyrrhic victory in Ukraine, Turkey will aim to fill in this vacuum.

The independence of the judiciary system and other bureaucracy will be reestablished after the destruction of this independence by the war between the elites during the revisionist period.

The anti-labour policies of the AK Party will continue

The economic liberalisation that started with Özal but damaged by the populist policies of AK Party will be resumed.

There are corollaries associated with each of these points. For example, the ambition to become the regional hegemon will require making peace with the Kurds and collaborating with a weakened Israel.

What I didn't foresee a year ago was the rapid unraveling of Erdoğan's regime.

The Rise of Erdoğan and the AK Party

As detailed previously, I believe a nation experiences growth only when the growth is pushed by an elite consensus. This consensus is not always easy to come by because growth involves risk for elites, as it threatens entrenched privileges. By "elites," I mean individuals and groups with significant influence over national dynamics. When I used to be a Marxist, I would define elites by their class, such as the bourgeoisie, feudal rentiers, etc. Today, I understand the composition of elites as more complex and more opaque. While unpacking their exact makeup is challenging, observing socio-economic and political narratives can reveal to me whether a consensus exists amongst a country’s elites, even though I may not know who exactly they are.

Young nations may lack well-defined elite structures. They struggle to achieve stable governance and growth. Built upon Ottoman remnants, the Turkish Republic inherited robust statecraft traditions from it. Some of these traditions may date back to Eastern Roman imperial rule.

My April 2024 post summarizes the evolution of Turkish elites over the last century, providing essential context for today’s developments.

The AK Party and PKK are the two last projects of the elites that started in 1980s. We now witness the confluence of these two projects. I believe the result will be a completely different Turkey.

The AK Party Project

In the 1980s, with elite backing, Turkey launched two significant political projects. Both projects were aligned at that time with the U.S. but was not instigated by US. The motivation was local and it was associated with the decision to switch from a mixed economy—dominated initially by state-owned enterprises—to a fully capitalist market economy. This switch required a dismantling of rural hegemony and relocation of rural populations to urban areas to serve as inexpensive labor. And the two projects were aligned with this requirement.

Rapid growth without compensating colonial revenues can only occur by suppressing wages. The Turkish experience is not too much different from the South Korean or Chinese experience. The workers do not happily agree to earn low wages in order to increase the returns for their bosses even when the bosses may be committed to invest these returns. In South Korea, the worker protests were suppressed with ruthless military opression including killing of thousands (with her poetic telling of these atrocities, Han Kang received the 2024 Nobel prize in literature). In China, the Communist Party discipline kept the workers’ alignment. The relations with the EU ruled out the first option for Turkey. At that time, one of the elite aspirations was to join the European Union. It would be difficult to maintain these aspirations if thousands of protesting workesr had to be killed to quell the opposition to economic growth. The Turkish elites decided to follow the Chinese modus operandi. They could not become communists of course, so the ideology that would provide the national cohesion was not communism but religion.

Religious sentiments run deep in the Turkish nation but were frowned upon in the first half century of the republic. The first project that started in 1980s had the objective to co-opt these sentiments to make the masses support the economic growth by working more at lesser wages. This was not the first time they tried this path but the earlier attempts to co-opt religion in support of the regime involved seculars adopting Islamist narratives without having a genuine change of heart. For example, the fiercely nationalist party MHP adopted the so-called “Turk-Islam synthesis” in 1960s and 1970s and inserted Islamist narratives into its party policies. I was in high school at that time and remember some partisans grumbling that this betrayed the shamanist foundations of the movement in 1940s. In spite of the extensive makeover, the public never embraced MHP as genuinely religious. Islamist factions supported Necmettin Erbakan at that time, who, despite multiple party closures, persisted politically because of the unvarying support he received from fundamentalists. However, an elite consensus around Erbakan’s leadership was difficult to form. Recognising this, Erdoğan, Gül, and Arınç left Erbakan and formed the AK Party. They even received crucial support from secular doyens of the Republican Party, such as Deniz Baykal, at the most critical moments.

The project succeeded. It succeeded politically because, unlike predecessors, the AK Party effectively maintained popular support despite harsh capitalist reforms, until recently. Its economic performance has produced mixed results but can still be described as success over the entire Erdogan reign. I will address this point later below, but let me first briefly talk about the second elite project of the 1980s.

The PKK Project

Turkey has a Kurdish problem. There are similarities with the Northern Ireland problem as I wrote in February 2024.

In 1970s, disparate democratic movements in Eastern and Southern Turkey, on those rare occasions when they moved together, produced a formidable Kurdish Democratic opposition. The 1980 military coup obliterated them. PKK was founded only a few years before the coup and its founder Ocalan had the amazing foresight to send PKK cadres to Syria a few months before the coup. They returned after the military regime made way for democracy again. With its cadres intact, PKK assumed a dominating position in Kurdish politics. Unlike the mass democratic movements of 1970s, PKK at the beginning was a terrorist organisation and this made it easy for the Turkish state to marginalise it.

Current Developments and Future Prospects

Both political projects—the AK Party’s religious-nationalist platform and the PKK’s insurgency—have run their courses. Erdoğan’s AK Party can no longer manage public dissatisfaction resulting from economic hardships, leading to a loss of popular support.

Simultaneously, the collapse of the Assad regime presents Turkey with both risks and opportunities. Without active Turkish involvement, Syria would risk becoming an adversarial state influenced by Israel. Turkey cannot control Syria while fighting the Syrian Kurds. Therefore, Turkey’s strategic interest lies in reconciliation with Syrian Kurds. But this is impossible without first resolving domestic conflicts with the PKK. This necessity motivated the fiercely nationalistic Bahçeli to issue, unsolicited, a call for peace negotiations last October.

I remain uncertain about the exact outcome of these negotiations. But I am certain that the outcome is not likely to extend Erdoğan's rule. Through potential legal maneuvers, Erdoğan may be a candidate again in the 2028 elections but I do not think he can win them.

Erdoğan’s Economic Legacy

I do not have ready to access to extensive economic data. Even if I did, I probably would not be able to interpret them properly. Therefore, I have to rely on analysis prepared by others.

An examination of Erdoğan's economic legacy, using data from Harvard University’s Atlas of Economic Complexity, reveals significant transformation. I suggest you visit the site and understand their methodology. In summary, they say that the Atlas results indicate that countries exporting complex goods typically enjoy higher income levels and stronger growth prospects.

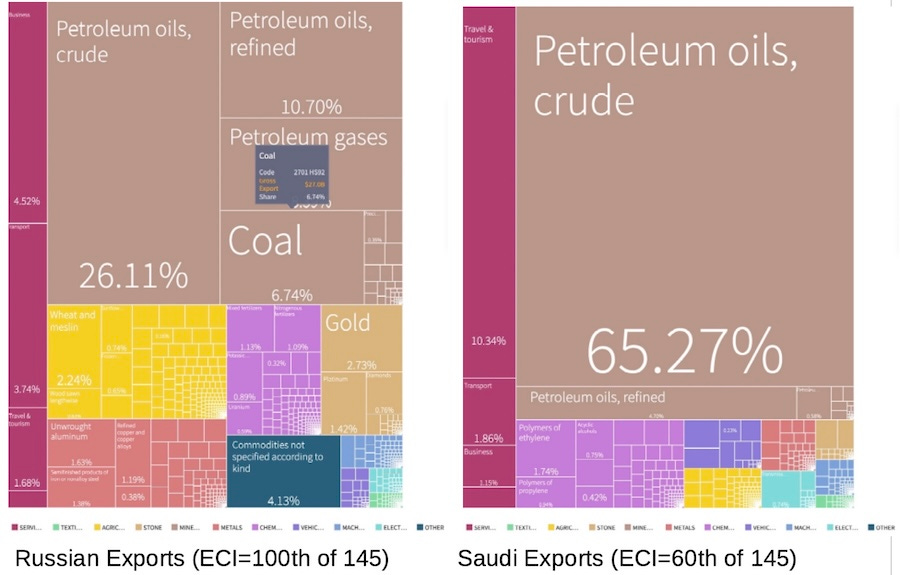

Exporting complex goods is exactly what it sounds like. For example, the Russian or Saudi exports are based predominantly on a few items and their forms the export complexity for these countries are low.

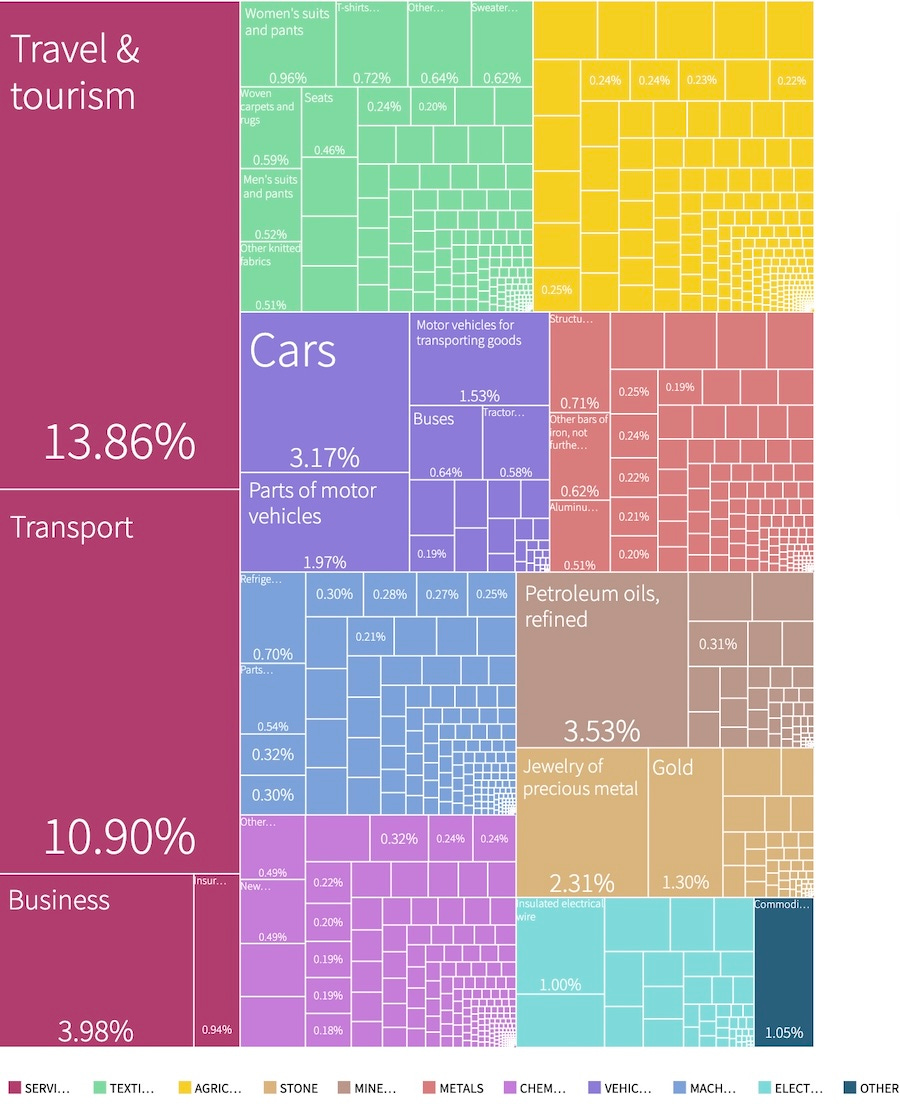

Both countries rely on fuel exports and Russia ranks 100th in the Atlas of 145 countries, and Saudi Arabia ranks 60th. In contrast, Turkey has a much more complex export composition and has the rank of 42 in 145 countries. The following is the composition of the Turkish exports. The contrast with the Russian and Saudi charts is obvious.

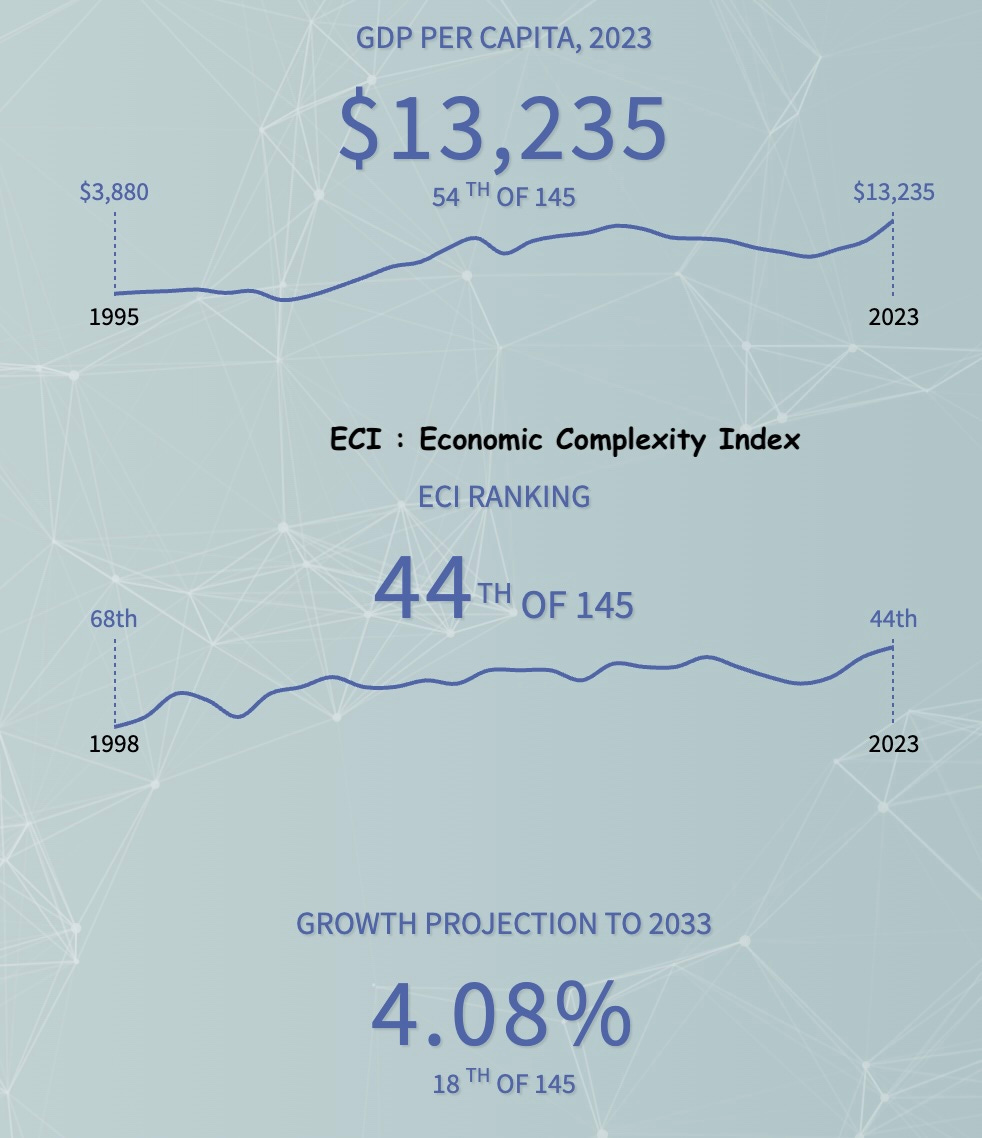

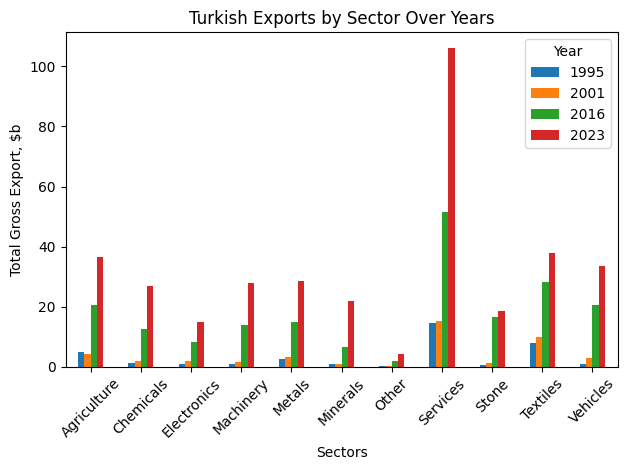

The export complexity experienced significant growth during Erdogan’s tenure as shown in the following summary

Turkey's export profile from 1995 to 2023 demonstrates substantial growth, especially in sophisticated sectors such as electronics, machinery, and automotive industries.

The Atlas concludes that Turkey’s economic complexity slightly surpasses expectations given its current income level, predicting moderate but steady growth. Specifically, Turkey is expected to achieve annual economic growth of approximately 4.1% over the next decade, placing it in the top quartile globally.

These economic achievements are mainly an outcome of Erdogan’s ability to maintain popular support while the workers kept receiving very little share of the economic growth. However, his magic seems to have finally run out as indicated by his inability to quell the recent public unrest.

In summary, Turkey stands at a pivotal moment. The unraveling Erdoğan regime and strategic recalibrations domestically and regionally suggest profound changes ahead, shaped by a new elite consensus and evolving geopolitical realities.

Final Notes

I am not a close follower of the Turkish political discourse but from the little I follow, I get the impression that the apparent dialogues are actually monologues where each side says their piece without feeling a need to address the opponent’s arguments, For example,

One side: Every one knows that 2 + 2 is 6.

The other side: But, you get 7 when you divide 24 by 3.

The third side: There are ten planets in the solar system.

I am very interested in receiving critical comments but I am hoping they will address the specific weaknesses and mistakes in my analysis rather than raising totally disconnected new arguments.

-+-+-+-+

Comparing Istanbul and Brisbane prices - AT index

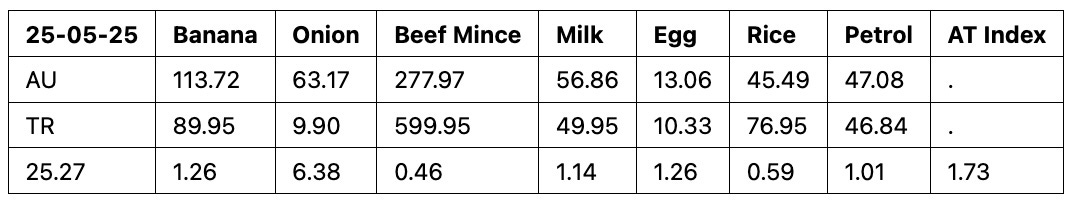

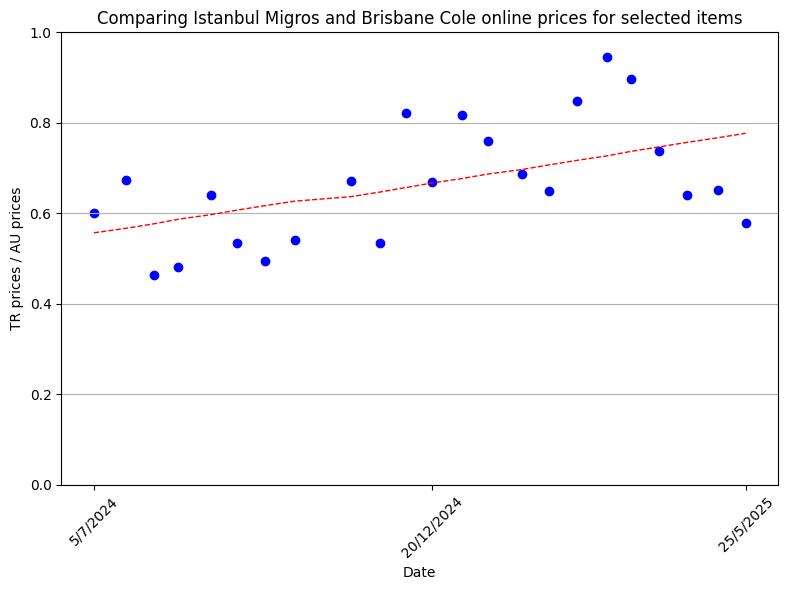

Based on my basket of goods, Australia is 53% more expensive this week compared to Istanbul. Both Coles (AU) and Migros (TR) prices are expressed in Turkish liras for the items in the basket on 11 May 2025. I converted Coles prices to Turkish liras at the exchange rate of 1AUD=25.27 TRY.

The trend (the red dotted line) is rising, which means that, since 5 July 2024, the Turkish prices have been slowly approaching the Australian prices. Some items, e.g. beef mince and rice, are more expensive than in Brisbane and has been consistently so since I started this chart.

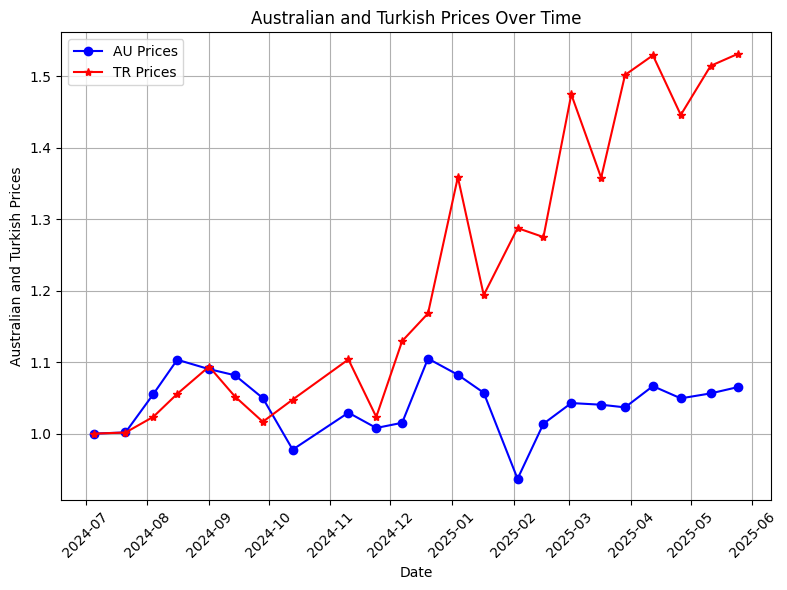

In this post, I decided to add two more charts. They represent the total cost for the basket in each country separately taking 5 July 2024 as the base.

The code to create the above tables and the chart is in my github repository and can be downloaded if you are interested.