Will there still be universities in 2050?

If universities survive until 2050, what will be their function in the emerging age of AI?

If you like what you read, copy and share the link, post it on another platform.

Please also subscribe to make sure you will not miss future posts. Subscription is free. Your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

-+-+-+-+

A month ago, I wrote about jobs and the future of work in the age of AI. I was planning to continue on this theme, focusing on the implications for the education sector. However, the pain in my right shoulder diverted my attention in the last post.

Shoulder Health Update

My shoulder is improving—not yet at 100%, but getting there. I want to sincerely thank all the friends who sent me get-well notes via email, WhatsApp, or comments.

According to my GP, the X-ray and ultrasound scans revealed no arthritic conditions. Instead, the diagnosis was bursitis, which is essentially inflammation of the bursa sacs. Additionally, there were calcium deposits in the muscles around my shoulder, particularly in the subscapular muscle. The ultrasound specifically identified a rather substantial calcium deposit, measuring 25 millimeters.

The good doctor advised that the condition might resolve naturally. He suggested physiotherapy to strengthen the upper arm and shoulder muscles.

When my physiotherapist measured my strength last week, my right arm was only 60% as strong as my left. For a right-handed person, the right arm should always be stronger. Our immediate goal thus became clear: restore the strength of my right arm. He gave me a training routine and we will assess the progress in two weeks.

With that update, let’s move to today’s theme—the effect of AI on the higher education sector.

Is AI rotting our brains?

Recently, I came across an MIT study involving three groups of students tasked with writing an essay or answering an open-ended general knowledge question. The first group was allowed to use AI tools such as ChatGPT or Gemini, and unsurprisingly, nearly all did use them extensively The second group was permitted to search the internet only using traditional browsing tools but no AI. The third group had no access to AI or the internet.

The researchers monitored students' brain activity, presumably using MRI or similar devices. I thought the results were predictable yet still interesting: students who relied on AI exhibited the lowest levels of brain activity. Those who used standard internet search showed moderate brain activity. Meanwhile, students relying entirely on their own cognitive resources showed the highest brain activity.

These findings have been broadly interpreted by media outlets as evidence that reliance on AI is making us intellectually lazy. The narrative is straightforward: if we don’t actively engage our brains, we risk cognitive decline—essentially, "use it or lose it."

This interpretation aligns with a broader narrative in Western societies, where there is a growing concern about excessively simplifying life for younger generations. Books like Jonathan Haidt’s "The Coddling of the American Mind" highlight similar issues, reinforcing the idea that sheltering or over-aiding young people might actually disadvantage them in the long run. The MIT study fits neatly into this broader societal concern, which is likely why it has received significant attention in the media.

Neal Stephenson

As I was reflecting on these themes, Neal Stephenson published a Substack post titled "Emerson, AI, and the Force," which I understand to be a transcript or summary of a presentation he gave at the Laude Institute Summit. Neal Stephenson, around twenty or more years ago, wrote a novel called "The Diamond Age," which featured an AI-driven educational device designed specifically for young children.

In "The Diamond Age," a wealthy man commissions a custom-built educational AI device for his granddaughter. Three copies are created and, by mistake, one finds its way into the hands of a young girl from a severely underprivileged background. At the start of the novel, she is approximately four or five years old and lacks access to basic healthcare, schooling, or any other supportive resources. The girl possesses remarkable innate intelligence and, with the assistance of this AI device, achieves significant educational and personal success.

When I read the book, I thought that a strong intrinsic motivation was the prerequisite for the girl's success. Without this motivation, regardless of how advanced or sophisticated the AI tool might be, little would likely have been accomplished. Neal Stephenson himself acknowledges this point. He notes that the other two copies of the educational AI device, intended for children in affluent families, did not yield similar success because those recipients lacked the motivation or necessity to fully utilize the technology.

Beyond these points, I found the remainder of Stephenson’s essay less insightful. Ultimately, he also thinks that AI rots brains and we should perhaps limit its role in education. Stephenson concludes: "You learn self-reliance through failure, and AI tools cause true failure as a malfunction. AI’s purpose, as currently configured, is to make things easy for humans, and humans who have had it easy from birth don’t have the grit to deal with challenges."

Thus, Stephenson seems to suggest that AI tools in education might hinder in cultivating resilience and self-reliance among young learners.

Academics View AI as a Nuisance

I discussed this topic with colleagues at my university and several others. With only a few exceptions, I found to my surprise that most academics have a very limited understanding of the transformative potential of AI. Their prevailing sentiment is concern over students potentially using AI to cheat, and a primary focus is on methods to prevent this. This attitude strongly reminds me of a similar controversy from around fifty years ago, when handheld calculators first became widespread.

In high school, I was taught to use logarithmic tables for complex calculations, and later, at university, we learned to operate slide rules. However, when calculators appeared, they rendered slide rules and logarithmic tables obsolete almost overnight. Initially, my university tried to prohibit calculators in examinations, but this proved futile. The lesson from this historical parallel is clear: when new educational tools emerge that simplify tasks, it’s more beneficial to embrace their use rather than resist.

Will Universities be able to Adapt?

If AI enables students to easily produce high-quality assignments more easily, we should raise our educational standards and make up new teaching objectives that harness AI, empowering students to achieve significantly ever more than before.

I anticipate that very soon, AI tools will enable students to master course content far more effectively than through traditional classroom lectures. AI tools will deliver instructional content and simultaneously assess students’ understanding, effectively functioning as both tutor and assessor. For instance, I am currently developing an AI-powered teaching and assessment tool for a course on Machine Element Design for second-year mechanical engineering students. Academics will naturally adopt these tools to ease their workload, freeing up more time for research or other tasks. However, this convenience may ultimately render the role of many academics obsolete.

You may push back and say that universities today function not only as centers of education but also as gatekeepers. They evaluate students’ learning and issue diplomas, effectively certifying their suitability for employment.

In fact, in certain fields like software engineering, this gatekeeping role is already outdated, as large technology firms increasingly assess candidates directly through proficiency exams rather than relying on diplomas.

If future AI tools can reliably interview candidates, ask relevant questions, assess responses, and accurately determine suitability for employment, employers will likely prefer these tools over relying solely on academic diplomas.

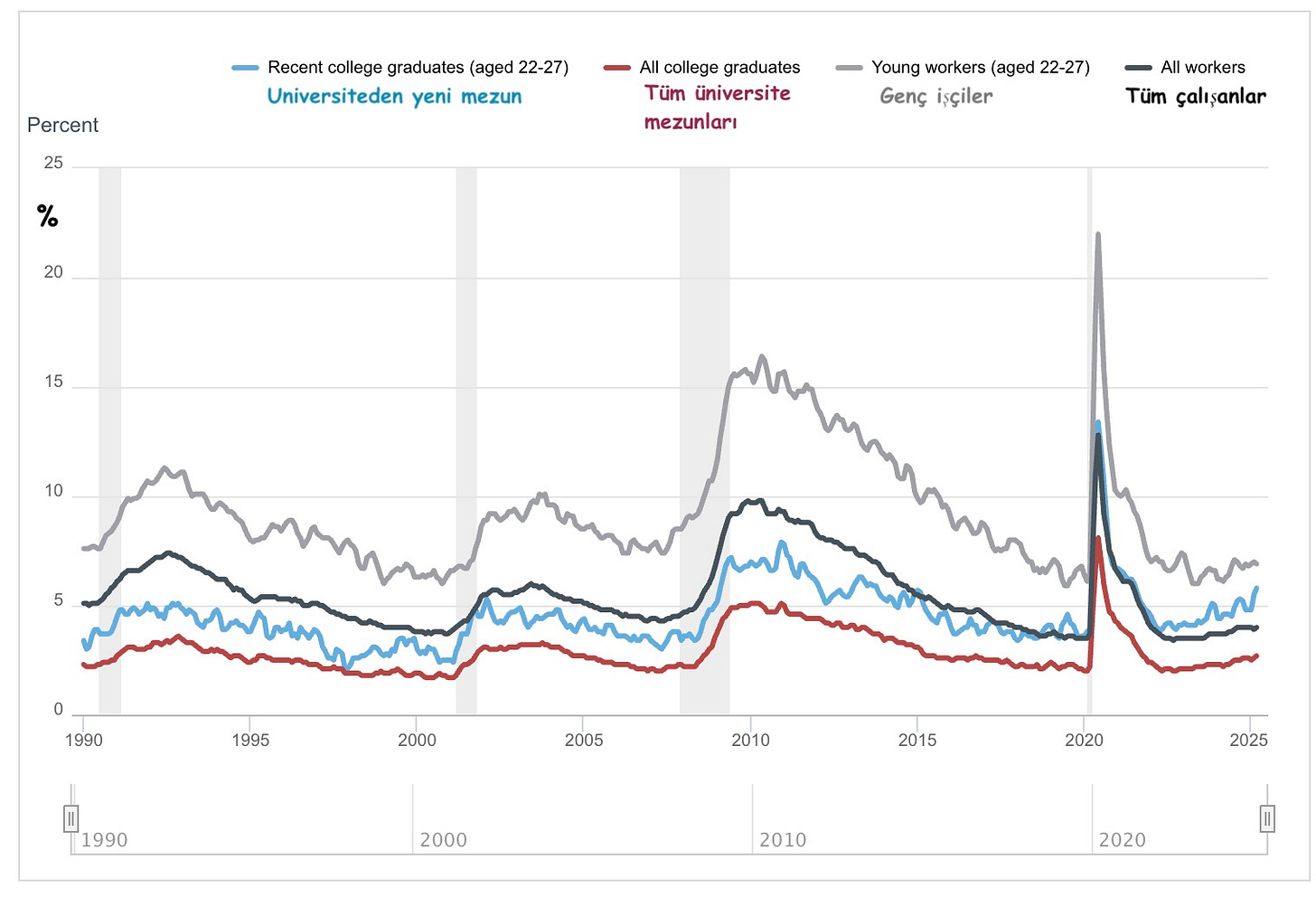

The following graph shows that this trend may have already started.

The unemployment rate in the above chart for new university graduates in USA is higher than the unemployment rate for all workers. For the first time in many years, having a university degree does not necessarily mean you will have a better chance of being employed than the average Joe.

I do not think business sector has changed. There is no reason to believe that most companies still prefer to hire skilled over unskilled. What this chart shows is that young people are probably starting to acquire those skills elsewhere, presumably through AI. Incidentally, this is happening at a time when the universities are experiencing a crisis in public trust. Recently, a Gallup survey found that American confidence in higher education has dropped to just 36%, plummeting from 57% just 9 years ago.

All of the above leads to a critical question: if AI surpasses university lecturers as educators and proves more reliable than universities as gatekeepers in assessing job suitability, what then becomes the purpose of universities?

Capable university administrators should already be pondering these challenges, yet I see little evidence of such proactive thinking. For example, my institution, the University of Queensland, recently released a five-year strategic plan committing to “Integrate UQ’s Artificial Intelligence Framework, enabling a balanced, risk-based approach to ethical use, academic integrity, and academic and professional productivity.” Unfortunately, this vague commitment provides little reassurance that the university leadership fully comprehends the profound changes that AI is likely to bring within the next decade.

-+-+-+-+

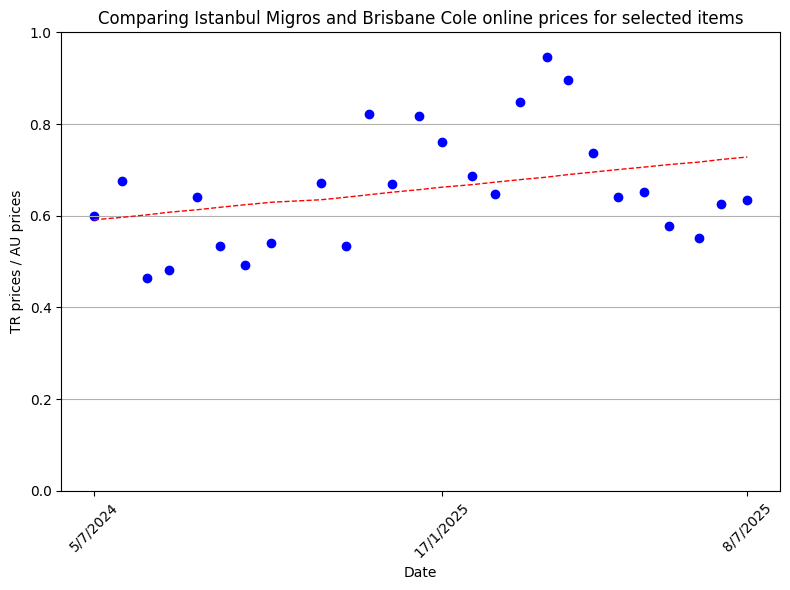

Comparing Istanbul and Brisbane prices - AT index

Based on my basket of goods, Australia is 60% more expensive this week compared to Istanbul. Both Coles (AU) and Migros (TR) prices are expressed in Turkish liras for the items in the basket on 8 July 2025. I converted Coles prices to Turkish liras at the exchange rate of 1AUD=26.17TRY.

Although the trend (the red dotted line) is rising, which means that, since 5 July 2024, the Turkish prices have been slowly approaching the Australian prices, it started flattening in recent months. Some items, e.g. beef mince and rice, are more expensive than in Brisbane and has been consistently so since I started this chart.

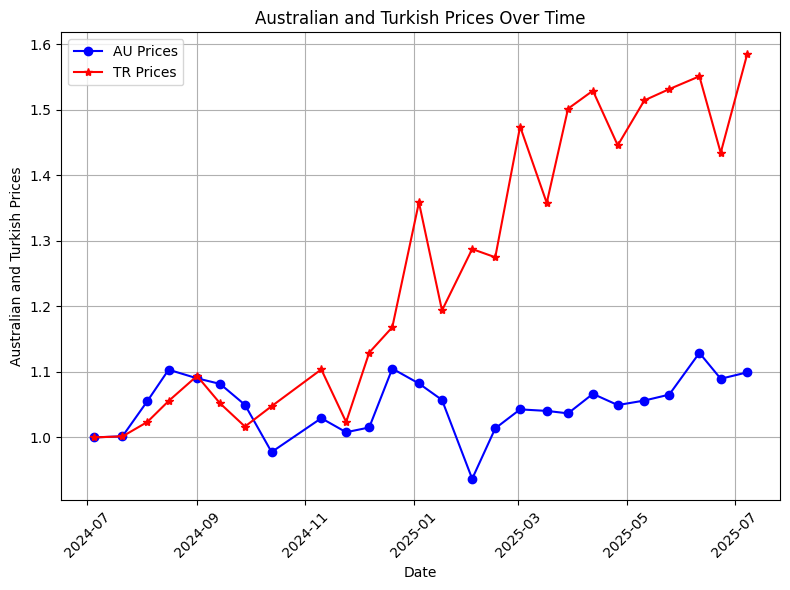

The following chart shows the variation of the total cost for the basket in each country separately taking 5 July 2024 as the base.

Wages

The Australian minimum wage was increased to almost $25/h on 3 June 2025. This corresponds to A$4000/month for a 160-hour month. The Australian workers being paid the minimum wage are about 2.6 million or about 18% of the total Australian work force.

The minimum wage in Turkey is 26,000 TRY/month. At the current exchange rate this corresponds to A$1018/month.

The code to create the above tables and the charts is in my github repository and can be downloaded if you are interested.