The Not-so-Hard Problem of Imitation Consciousness

The promise and limits of our immortal avatars in preserving our identity for our ancestors

If you like what you read, copy and share the link, post it on another platform.

Please also subscribe to make sure you will not miss future posts. Subscription is free. Your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

-+-+-+-+

We do not know what consciousness is and probably will never know but we know what conscious beings do. If we know what they do, we can imitate them.

Can a Digital Avatar Be Conscious?

In the last post, I explored the idea of digital avatars as a way to leave a digital legacy for future generations. These avatars would be digital copies that look, think, and respond like us. I ended the post with a few open-ended questions:

What would it feel like to be the copy?

Even if it talks and behaves like a conscious being, would it actually be conscious?

How different would it be from me?

Let us dive deeper into these equations and speculate.

This is the second part in a series. Please read the first part first if you have not done so yet. It is here:

What is consciousness?

The short answer: No one knows.

We’ve made tremendous progress in understanding the brain’s physical processes—attention, perception, memory, and behavior. David Chalmers calls these the “easy problems” of consciousness. Technologies like fMRI help us map which areas of the brain activate when we experience joy, listen to music, or savour food. But none of this explains how subjective experience (qualia)—the “what it feels like” aspect—emerges from brain activity.

In 1995, Chalmers coined the term “the hard problem of consciousness” to describe the difficulty of explaining this subjective experience. The phrase has since become part of the standard vocabulary in discussions about consciousness.

As an engineer, I tend to theorize based on observations of the physical world. I define consciousness as the sum of observable behavior patterns exhibited by conscious beings. I know I’m conscious, and I assume the humans I interact with are too. Based on this assumption, I can model human behavior patterns and create digital simulations.

How Good Can These Copies Be?

We can evaluate how well a digital copy simulates a person by comparing its responses to stimuli—questions, pictures, or music—against the responses of the original person. If the simulation consistently produces similar answers, even in novel scenarios, we might consider it a successful copy.

Today, creating such high-quality simulations is technically possible, though expensive. If enough effort is invested, these digital avatars could become indistinguishable from the originals in terms of observable behavior.

But here’s the catch: purists argue that these simulations, no matter how advanced, will never truly possess consciousness. After all, they are just mathematical models imitating behavior.

However, since we don’t know what consciousness really is, this objection is irrelevant. Instead, the better question to ask is: Do these avatars respond to stimuli in a way indistinguishable from the original person? If the answer is yes, it might not matter whether they are “real” or just an imitation.

To illustrate this, let me draw an analogy from mechanical engineering.

Simulation of Fluid Flow

Aeroplane manufacturers need to predict how planes behave under various wind and flight conditions. Fifty years ago, when I was a student, the only way to do this was by building wind tunnels. Computer simulations were theoretically possible, but they were impractical.

The behavior of fluids (like air) is governed by the Navier-Stokes equations, a system of complex differential equations. Solving these equations for something as intricate as air flowing over an aeroplane’s wings is still computationally impossible, even today. Instead, we rely on approximations. For instance, companies like Feynman Aerospace create simulations good enough to predict real-world behavior without expensive wind tunnel tests:

However, the computers are getting more powerful every day and they are generating better and better simulations. Now imagine two rooms, in the near future. In one, a person is on the phone talking to a pilot flying a real aeroplane. In the other, a computer runs a highly detailed simulation of the same aeroplane. Both rooms are tasked with answering this question: “What happens if the aeroplane suddenly takes a 10-degree dive at 900 km/h?”

• The person in the first room relays data collected from the real flight.

• The computer in the second room generates a simulated response based on its model.

If both answers are identical for this and every other scenario, does it matter whether the data came from the real aeroplane or the simulation?

Simulation of Consciousness

The same principle applies to digital avatars. While we may never know what consciousness truly is, we do know how conscious beings behave. If we can imitate that behavior well enough, the simulation becomes functionally indistinguishable from the real person.

Imagine two screens in front of you, each showing a talking head. One screen displays me, speaking live into a camera. The other displays my digital avatar. You’re not told which is which. As we engage in a three-way conversation, you can ask us questions and judge our responses.

This setup resembles the original Turing test, but with voice and video instead of text. If you can’t reliably distinguish me from my avatar, then the simulation is a competent imitation of me. It may not be conscious, but it can still serve the purpose of representing me to future generations..

Avatar consciousness

Passing the Turing test doesn’t mean the avatar is conscious—it only means it’s a good imitation of a conscious being. Asking the avatar directly if it’s conscious won’t help, because it would respond just as I would and might say yes.

But does it really matter? The goal of the avatar is to represent me to my great-grandchildren and beyond. If it succeeds in doing so, then whether it’s conscious or not becomes a moot point.

The imitation will be an imitation of the actions not the internal processes. For example, the avatar will demonstrate the same taste of music even though it cannot appreciate music as I do. I hear music through my ears. The avatar will “hear”music as digital files and complex spectra. Having enough data on my music taste, it will be able to construct algorithms on what kind of “spectra” I will like. Using this algorithm, it probably will be able to decide whether I would like a new song or not.

Immortality

Building a digital avatar is not a pathway to immortality. Even if the avatar were somehow conscious—whatever that means—it wouldn’t be me. When my physical body dies, my consciousness, as far as we understand it, will cease to exist.

The avatar might live on forever, but it would only be an echo of who I was, not my true self.

This exploration raises as many questions as it answers, but one thing is clear: while digital avatars may not grant us immortality, they have the potential to preserve a meaningful representation of us for future generations. And this may be enough.

References

Chalmers, D. (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3):200-19.

-+-+-+-+

Short Takes

Vice-Chancellor Salaries and Accountability

Guardian, 21 November 2024

An investigation by the National Tertiary Education Union revealed that senior university administrators across Australia are earning salaries significantly higher than the premiers of their respective states.

Last week, I visited a university in New South Wales that is in deep financial trouble. The Vice-Chancellor1 (VC) responsible for the crisis resigned earlier this year, and an interim VC was appointed in their place. One of the interim VC’s first actions was to sack 90 academics, with more redundancies expected in 2025. A similar situation is unfolding at a university in southern Queensland (not mine).

Having worked in both the private sector and universities, I’ve noticed a stark difference in accountability. In the private sector, it’s considered deeply embarrassing for a CEO to announce mass redundancies—it signals a failure of foresight and leadership. Yet, university administrators appear to show no such embarrassment. Instead of acknowledging past mismanagement, they blame external factors like COVID and government policies for the crises they face.

ICC issues arrest warrant for Netanyahu

Semafor, 21 November 2024

The International Criminal Court on Thursday issued arrest warrants for Israel’s prime minister and Hamas’ military chief over alleged war crimes. The court said it was “reasonable” to believe Benjamin Netanyahu and other Israeli leaders committed “inhumane acts,” including using starvation in warfare — accusations that Israel rejected as antisemitic.

Several countries including Canada (but not Australia) said that they follow the ruling, which means that they would arrest Netanyahu if he enters their country.

This makes me angry and sad for Israel. Israel deserves much better than being put into this international pariah position.

It was not difficult to predict this. Last year, straight after Israel announced that they were invading Gaza, I wrote that “another solution must be found to punish Hamas without causing the deaths of many more innocents. This is not only for the sake of the Gaza population but also for the future of Israel. I hope the friends of Israel will make them to recognise this fact.” Alas, this did not happen.

-+-+-+-+

You Tube

A noticeable shift in the Australian government’s attitude towards China began about ten years ago. Around that time, I was an elected member of the University of Queensland Academic Board. In one meeting, we were advised to exercise greater caution in our scientific and academic collaborations with China. The stated reason was to protect Australian intellectual property.

I remember raising my hand to point out that, in my experience, Chinese partners often had access to greater resources, including staff and laboratory infrastructure. If anything, it seemed like the Chinese should be more concerned about protecting their intellectual property. My comment was met with polite dismissal by the Vice-Chancellor, and it became clear that this directive wasn’t his initiative—it was coming from the Commonwealth government.

Since then, attributing hostile intentions to the Chinese government and advocating for pre-emptive measures to guard against these hypothetical threats have only increased. Unfortunately, China’s often clumsy diplomatic efforts haven’t helped de-escalate the situation.

This growing tendency for “China bashing” deeply worries me. In my view, the greatest challenge facing humanity in the near future is avoiding a war between the United States and China. In the following YouTube video, Professor Jeffrey Sachs argues that the real threat isn’t China itself, but rather an insular, hawkish faction within the U.S. administration.

The only plausible pushback (in my opinion) to Professor Sachs’ arguments are made by another American academic, Professor John Meersheimer. You can watch the following All-In podcast discussion between two after watching the above.

-+-+-+-+

Diary

Last week, I had to travel to Wollongong, a city of 216,000 people that doesn’t have its own decent airport due to its proximity to Sydney (only 60 km away). My hosts booked me a flight to Sydney and a rental car to drive to Wollongong.

The journey began smoothly. I took an Uber to Brisbane Airport. While Uber is only slightly cheaper than a regular taxi, its app is so convenient that I’d use it even if the price were the same. My driver shared some interesting insights during the ride. He explained that Uber takes 27.5% of his earnings—a hefty margin, especially since Uber doesn’t contribute to the car’s expenses. He wasn’t overly bothered by the percentage but expressed frustration with sudden changes in Uber’s policies that affected his income. For instance, Teslas used to qualify as luxury vehicles and attracted higher fares until last year. Now, they’re classified as regular cars. Similarly, his own car, a 2016 Mitsubishi Lancer, had recently been downgraded from “Comfort Car” status to a standard vehicle. Despite his grievances, the drive to the airport was pleasant, and I arrived on time for my 3 p.m. flight to Sydney.

Unfortunately, that’s where things started going downhill.

The flight was initially delayed by an hour due to stormy weather at Sydney Airport. We eventually boarded around 4 p.m., but shortly afterward, we learned that no planes were being allowed to land in Sydney. Once you’re on board, though, you’re stuck—they don’t let you disembark. So, we sat there for two hours, waiting. Finally, the plane departed around 6 p.m. and landed in Sydney at 8:30 p.m. local time (an hour ahead of Brisbane due to daylight savings). It was still raining and windy when we arrived.

After waiting 15 minutes for the rental car shuttle, I arrived at Avis, where a Tesla awaited me. I mentioned to the attendant that I’d never driven a Tesla before. Her initial reaction—a worried “Oh”—didn’t inspire confidence. She reassured me, though, saying it was easy to operate and offered to show me the basics. In the pouring rain, she demonstrated how to open the driver’s door by sliding a plastic card around the frame. Inside, the only control I could immediately recognize was the steering wheel. A small lever extended from the wheel, with a button at the end that toggled between P, D, and R. She quickly explained this and left.

What followed was 15 frustrating minutes of trying to start the car. No matter what I pressed or swiped, I couldn’t make it move. At times, the car’s image appeared on the large dashboard screen, complete with animations that made it look like it was ready to go—but it never actually responded. Realizing this was ridiculous, I returned to the counter and asked for a regular car. Luckily, they had a Mazda SUV available. Its controls were familiar, similar to Meliz’s Mazda MX5, so I was able to get it going right away.

However, the drama didn’t end there. The Mazda’s built-in navigation system refused to recognize “Novotel Wollongong” as a destination. After five minutes of fiddling, I gave up and used my phone for directions. I finally reached the hotel around 11 p.m.

Once there, I parked in the hotel’s basement and tried to take the lift up to the reception. The lift refused to move because I didn’t have a room card, which, of course, I couldn’t get until I’d checked in. So, I walked back up the incline to the surface and entered the hotel through the front door, which thankfully was still open. Check-in went smoothly, but adding my car’s registration number to my room account took another five minutes. Novotel had outsourced its parking operations, and the two systems didn’t seem to communicate well.

The morning after

The next morning, the sky was starting to clear, though it was still windy. During breakfast, I noticed a pigeon taking shelter just outside the hotel—a small moment of calm after the chaotic travel.

The rest of the trip went smoothly, and the meeting was a success. Here’s a glimpse of my time on campus::

A Farewell Lunch

On Monday, before heading back to Sydney Airport, we had lunch at The Lagoon restaurant. It was a beautiful spread of the best seafood Wollongong’s coast has to offer—a perfect way to end the trip.

-+-+-+-+

Pascal Hagi

Before Pascal’s great escape (and eventual comeback) in early 2023, he had free run of the house. One of his favorite spots was the kitchen sink, where he could enjoy the view from the window.

Now, with his new friend Hagi and the outdoor aviary we built for them, Pascal spends much less time indoors—even when I leave my office door open.

Here’s a rare moment they both ventured inside and settled on the kitchen sink, captured in the following YouTube video:

-+-+-+-+

What I Read

John Le Carre

Call for the Dead, A Murder of Quality, The Spy who came from the Cold

John le Carré, who passed away on December 12, 2020, at the age of 89, began his career writing spy novels but grew to become much more than just a genre author. Vanity Fair aptly called him “one of the best novelists—of any kind—we have.” I wholeheartedly agree.

Le Carré’s most iconic creation is George Smiley, a complex and brilliant spy, who appears in several of his novels. I first encountered Smiley when I read Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy as a student in Ankara during the 1970s. I borrowed it from the British Council Library. At the time, my English was poor, and I had plenty of distractions, yet I still loved the book. Over the years, after moving to Australia, I read nearly all of le Carré’s works, but Smiley remains my favorite character.

Last month, I learned that Nick Harkaway, le Carré’s son, has written a new George Smiley novel titled Karla’s Choice. Harkaway is an accomplished writer in his own right. I had already enjoyed two of his books (The Gone-Away World and Gnomon) before I discovered he was le Carré’s son. In interviews, Harkaway admitted he was nervous about continuing his father’s work. He even sought advice from Joe Hill, Stephen King’s son, who also expanded on themes from his father’s stories.

Harkaway’s new novel takes place after the events of le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and before Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Before diving into it, I decided to revisit the first three George Smiley novels—starting with le Carré’s debut.

Call for the Dead

George Smiley is introduced in le Carré’s first novel, Call for the Dead. Smiley is a scholar by nature and training, recruited into British Intelligence while at Oxford. He’s sent to Nazi Germany under the cover of a university lecturer, where he demonstrates an exceptional talent for recruiting and managing spy networks. After the war, he returns to London for an unassuming desk job. However, he finds himself drawn into a murder case that he suspects is connected to the East German spy agency—though his boss sees it differently.

A Murder of Quality

Le Carré’s second book, A Murder of Quality, isn’t a spy novel at all. It’s more of a detective story featuring Smiley. While interesting, it’s not essential reading if you’re primarily interested in le Carré’s espionage work. You can safely skip this one and move on to his third novel.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold

This is the book that made le Carré famous, selling millions of copies and spawning several film adaptations. It opens with a gripping scene at a Berlin checkpoint, where East German guards shoot a West German spy as he tries to escape to the West.

Published in 1963, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is set against the backdrop of the Berlin Wall, which had been erected just two years earlier in 1961. In my view, the construction of the Wall marked a turning point in Western attitudes toward the Soviet Bloc. Before then, the Soviet experiment was viewed with some sympathy in parts of Europe, partly due to Russia’s immense sacrifices during World War II and partly as a reaction to the excesses of McCarthyism in the United States. But the Berlin Wall changed everything—it became difficult to admire a regime that had to build a wall to trap its own citizens.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold captures this shift in sentiment brilliantly, offering a bleak, cynical view of Cold War espionage. It’s no wonder this book launched le Carré into literary stardom.

Looking Forward to Karla’s Choice

Once I finish rereading The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, I’m eager to dive into Nick Harkaway’s Karla’s Choice. I’m curious to see how he continues his father’s legacy and how he breathes new life into George Smiley.

-+-+-+-+

Ratio of Brisbane/Istanbul prices — AT Index

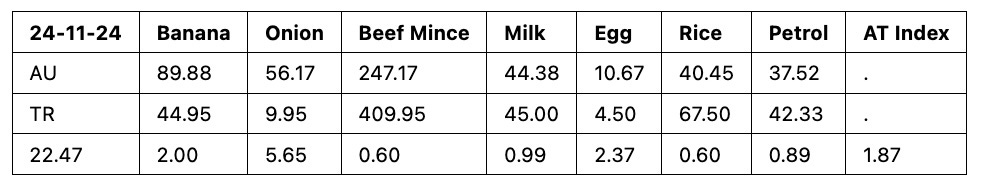

Based on my basket of goods, Australia is 87% more expensive this week compared to Istanbul. Below are the prices in Turkish liras for the items in the basket on 24 November 2024. The exchange rate is 1AUD=22.47 TRY.

The following is the plot of AT index. The height of the bar represents how more expensive Australia is.

It is interesting that for the basket of goods I have, the ratio between the Australian and Turkish prices have not changed much since the beginning of July 2024, when I started doing this. Most of the fluctuations are due to the exchange rate changes. The code to create the above tables and the plot is in my github repository and can be downloaded if you are interested.

The Australian Vice-Chancellor is equivalent to the American University President or the Turkish University Rector. In Australian universities, the role of Chancellor is unpaid and mostly ceremonial.

If yu want to understand what made him famous, I think you should read a cold war spy book like Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. He stopped writing cold war spy books after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc.

His later books have more dimensions and you may enjoy them more. I suggest Constant Gardner. It is a topical book and is a story on the big pharma shenigans in poor African countries.

Afterwards, you may decide to read his other books.

Dear Halim,I do not agree with your strained definition of 'consciousness' based on observing behaviour. It is very difficult to to define consciousness., but I have a simpler definition. Consciousness is awareness of self and all the other things in the universe. In my opinion this property belongs only to living things. We can observe the behavior of oxygen atoms. When they come into contact with hydrogen atoms they form water. Are they aware of this behaviour, do they feel any desire for this reaction? However when a sheep is grazing it is very much aware of eating grass. I am not looking forward to having a digital copy which can imitate me perfectly after my death. Many people are enviously waiting for developments in medicine which will prolong human life to 200 years. This is unbearable for me. Shall I start working again to make a living? Death is a gift given to living things. Compared to eternity 100 years, 200 years, 1 million years are all zero. Thank you for sharing your views.Best greetings.