Nuclear power no fix for our broken grid

This is about the proposal to build seven nuclear plants in Australia. Read carefully even if you are not an Australian, it concerns you too unless you live in Canada, Mexico or Sweden.

Please subscribe; please share. This blog will always be free but worthy reading. There is no downside to subscribing because your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

Copy and share the link, post it on another platform. It is not that I get money with more subscribers, but it makes me happy when more people read it.

-+-+-+-+

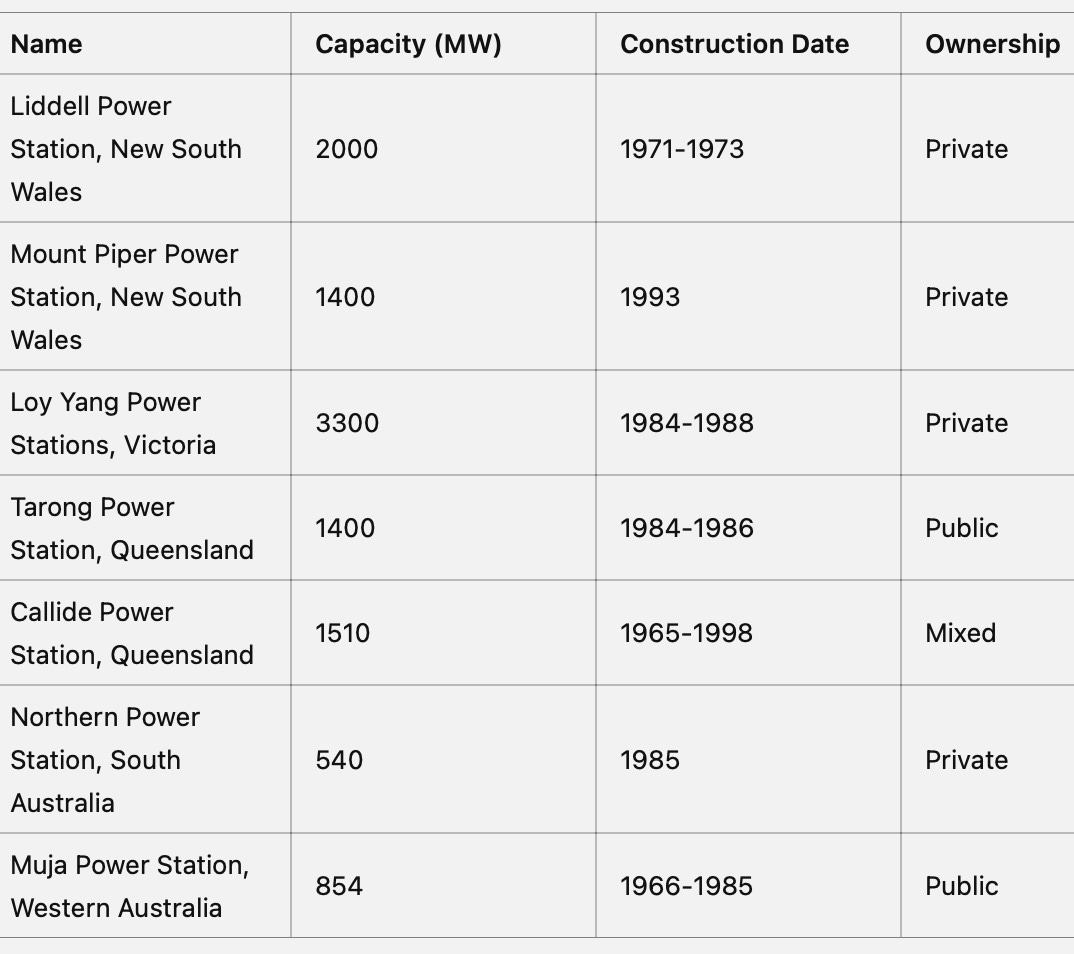

On 19 June 2024, Peter Dutton, the leader of the Australian Opposition1 announced that, if they win the power at the next election, the Federal Government will build large nuclear power plants (NPP) at seven existing coal fired plant sites2.

Australia has two electricity grids. The Eastern grid is larger and is called the National Energy Market (NEM). It has a total installed capacity of 55GW. Six of Dutton’s seven future NPP sites are in the Eastern grid. If they are similar in size to their predecessors, the new generators will be injecting over 10GW into the NEM.

The NEM grid is facing stability and reliability problems as the share of cheap renewable into the grid is increasing. Dutton says his NPP will limit future electricity price increases and will increase the grid reliability.

The criticism of the Dutton proposal in the press focussed on its cost by referring to two recent reports (GenCost 2024 and the NetZero). Both reports agree that nuclear power is too expensive compared to the alternatives.

I would like to raise a more fundamental point here. I do not think it is the choice of nuclear that makes the Coalition proposal expensive. Even if Dutton had proposed seven new coal-fired power plants instead of nuclear, it would still be very expensive.

The high Australian electricity prices are invariably but mistakenly blamed on the renewables. I copy from a recent IPA Press Release: “… any system built on baseload generation, like gas, coal, or nuclear, will always be significantly less expensive than one reliant on variable renewable energy.” One can find similar statements in the political discourse. I think some on the left side of the politics tacitly agree with this assertion but they argue that, even if it is true, this is a pain we need to endure to fight climate change.

There is a problem with this view because as I will show below, the problem gets worse as renewables get cheaper. We will see below that the electricity prices are inversely correlated solar panel costs. If we want to blame renewables for the higher electricity costs we should say that the renewable electricity became so cheap that it made the legacy generators too expensive because of our grid structure.

The real reason for the very high electricity prices we are suffering is the confluence of cheap renewables with a decision we made in 1990s. At that time, we decided to deregulate and privatise our electricity industry. We were following the example of UK, where privatisation of the electricity sector had been one of the last acts of the Thatcher governments.

It is true that cheap renewables paradoxically triggered higher electricity prices. But it did not have to be this way. It happened as it did because cheap renewables were introduced into grids where the electricity mix is set by instantaneous auctions rather than by long-term planning and optimisation.

It is not the cost of nuclear that makes the Coalition proposal costly. Replace nuclear with coal in the proposal, it would still be costly. The private sector already knows this. The banks will not finance a coal-fired power plant project in a deregulated market because such plants are no longer competitive against the cheap renewables. In fact, this is the reaason why the Coalition wants the government to build the new seven generators. Commercial companies would not do it because they would consider them as loss-making projects.

The dilemma with renewables is that they are cheap enough to make all base load generation uncompetitive. On the other hand, they are intermittent and when you add the cost of storage they become expensive. This dilemma has proved to be impossible to resolve in a deregulated privatised market and will remain to be so until storage issue is resolved. Our grid is broke and it will not be fixed by adding nuclear into the mix.

Who broke the grid?

When I first came to Brisbane in 1982, there was a State Electricity Commision (SEC). Owned by the State Government, it was responsible for planning, investment, operations, reliability of supply and tariffs in the State of Queensland. SEC commissioned one of my early projects at the University of Queensland Solar Energy Research Centre in which I explored alternative energy sources to generate electricity in Queensland outback towns and homesteads3. These were the years when the PV was not an option yet because it was too expensive. I specifically mention this exercise because it demonsrates the proactivity of the state-owned SEC in exploring alternatives to increase the robustness of the supply. The situation was similar in other states.

Thatcher privatised the UK electricity sector in 1990. Other OECD nations followed suit. The argument for privatisation was that private firms were more efficient and this would lead to cheaper electricity. The financial difficulties of the state-owned firms were raised as another argument4.

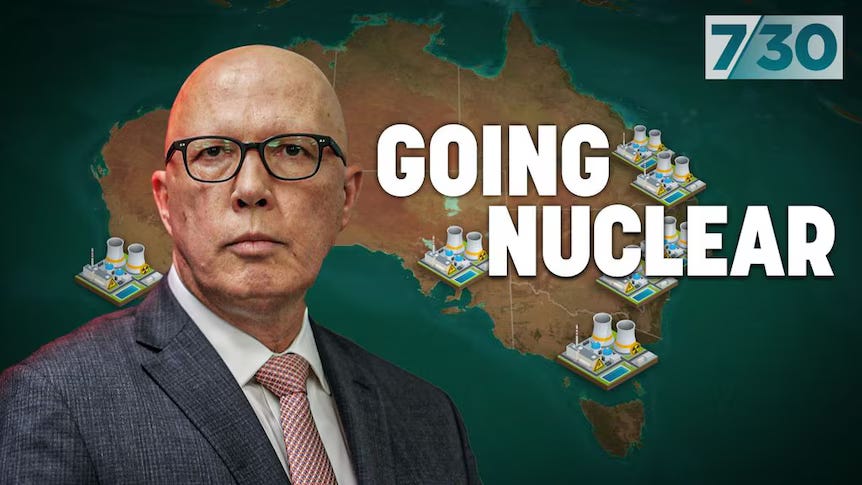

At first, Queensland electricity prices stayed relatively stable. There was a period of modest increases through the late 1990s and early 2000s. From around 2007-2008, however, prices began to rise more steeply. The steepest increases occurred between 2007 and 2015. After 2015, the rate of increase slowed. Overall, the post-privatisation price trend since 1990 has been upward, with the result that current prices are significantly higher than what they were then.

The following chart from a Statista post by Katharina Buchholz shows the electricity and gas price variation in that period:

As seen in the chart, the electricity prices rose almost five-folds in a period the CPI (Consumer Price Index) only doubled. This phenomenal increase in electricity prices must have embarrassed the proponents of privatisation debate. Initially, they argued that the increases were temporary and the prices would fall once the changes penetrated through the system. When this did not happen, they stopped talking about the prices altogether. Today, the economists investigate the competitiveness of the electricity sectors in terms of an “efficiency” parameter, which interestingly is defined in a way not related to the price of the electricity. An even more interesting (interesting in the context of the Chinese proverb) is that at the time the grid privatisation and deregulation policies were being implemented through the Western world, there was almost no disagreement between the economists on this policy. They all thought it was a winner.

How come a whole generation of economists erred so comprehensively? I am sure part of it was the greed, or the prospects of the deals the finance sector could earn their commisions on. But the consensus cannot be explained by greed only. I think it was the rate of technology change that caught the privatisers short. No one foresaw at that time how quickly the renewables like solar and wind would become competitive and upend the existing generation business,

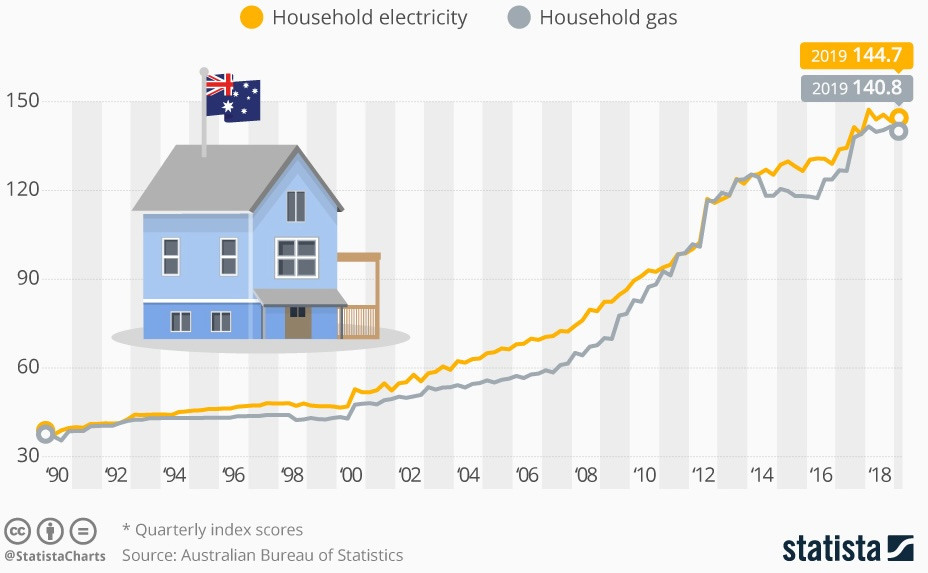

In 1980s, the choices of generation technologies were limited to three: coal, nuclear, and hydro when available. There was not much gas at that time and certainly very little solar and wind. If this array of choices had remained the same, the effect of privatisation would probably be limited and benign. The prices could have even come down a little bit, although I doubt it. However, the technological change was inexorable as unpredictable. The cost of solar and wind started coming down drastically in 2000s. Figure 3 shows the reduction in the solar panel prices. The wind is not dissimilar.

Now compare Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows that around 2007, electricity prices started increasing sharply. Figure 3 shows that around the same time the solar panel prices started decreasing sharply. This is not a coincidence. When solar electricity became competitive with conventional generation methods, the nature of the business changed. The results were disastrous for the privatised grids. To understand why this is so, we need to examine how the prices are set in a privatised grid.

In a deregulated grid, electricity generators bid into the market, offering to supply electricity at various prices. The market regulator accepts the bids starting from the lowest, and continues with higher and higher bids until the hourly demand is met. Everybody, even the lowest bid generator, is paid at the same unit cost, which is equal to the highest bid accepted into the mix for that hour.

More and more PV plants were built as the cost of the solar panels got less. The marginal solar generation cost is zero. On a good day, a solar PV plant will always be able to bid the lowest price. This means the market operator will use the solar supply first and call in the coal-fired power generation if and only if the solar and wind cannot meet the demand. The consequence is that only a fraction of the coal-fired power plant capacity will be used at any time of the day while the sun is shining.

Moreover, the solar and wind generators are paid at the highest bid, which is way above their marginal generation costs. This makes them more profitable and more solar and wind plants are built to share these profits. The fraction of the fossil-fired generator capacity in use gets smaller and smaller. The existing coal-fired and gas-fired generators become less and less competitive. They have to increase their price bids. This increases the income of the solar and wind generators even more because they still are the least-cost producers that get paid at the level of the least competitive generators.

In summary, the grid privatisation initiative was conceived in 1980s in the United Kingdom in an environment of relative technological stability. The privatisation turned into a disaster when the advent in zero-marginal cost technologies such as solar and wind changed the initial paradigm. Depending where they are in the supply mix, some generators can now barely stay alive while others reap exorbitant profits and the market operators keep trying to control the situation by continuously fine tuning the existing regulations and issuing new ones. This is not sustainable.

As a final note, I must admit that integration alone is not a panacea. Even the integrated grids find it difficult to deal with rapid technological change. For example, I read last week that there is significant excess in certain days in China but this excess is wasted because there is not enough storage facility. China is now considering ways to reduce the strain on the grid, including lowering energy prices during periods of high supply but low demand. Even in an integrated publicly-owned grid it will take continuous tuning but my point is that such tuning is conceivable and possible. Under the present circumstances in Australia and most of the Western countries that implemented the Thatcherite policies of the 1980s, all we do under the guise of fine-tuning is chasing our tails and blame the renewables (i.e. blame the technological change).

Conclusion

The Coalition proposal to build seven nuclear power plants (NPP) will not fix the structural problem of the grid as I tried to explain above. Unless, using its sovereign authority, the government decides to curtail all cheaper electricity to prioritise the NPP dispatch, the capacity factor for the NPPs will be low and they will be loss makers. The situation would have been the same if the Coalition build seven coal-fired power plants instead of NPP. When electricity prices are set by auction, the renewable power generators with zero marginal costs will always triumph over the fuel-burning generators. Unfortunately, at the moment, we are relying on fossil-fired generation to produce electricity when solar and/or wind are not available because storage is expensive. This is a devilish dilemma. Admittedly, the dilemma will disappear when we develop cheap storage, be it mechanical (like compressed air or hydro), or chemical (like hydrogen) or electrochemical (like batteries). But until then, we need to be able to optimise our generation offers to minimise the cost of electricity. Such optimisation is not possible in a market-driven system.

If the politicians really want to reduce the electricity prices, they should find a way of going back to the centrally planned vertical integration of 1980s, at least for a period of time until storage costs come down. When we have cheap seasonal storage, there will be no need for us to keep uncompetitive fossil-fired or nuclear power plants around. Then we can reintroduce competition into the grid because at that time the technology choices will have become relatively stable again although at a technology mix completely different from 1980s.

Counterfactual

People who know better than I do about these matters choose not to address this issue at all when analysing future scenarios. Net Zero Australia is a partnership between the University of Melbourne, the University of Queensland, Princeton University and international management consultancy Nous Group. Launched in 2021, the study investigated how Australia can achieve net zero emissions. The final modelling results published on 19 April 2023 presents a detailed breakdown of possible scenarios. They obviously believe that those scenarios are all doable in our present electricity grid structure. I disagree.

References

Paul, S., & Shankar, S. (2022). Regulatory reforms and the efficiency and productivity growth in electricity generation in OECD countries. Energy Economics, 108, 105888.

Short Takes

-+-+-+-+

Is Natrium the future of nuclear power?

Georgia Power Vogtl 3 and 4 are the only US nuclear power plants built in US since 1990 and may be the last nuclear power plants based on PWR (pressurised water reactor) technology. Vogtl 3 started generating power last year and Vogtl 4 on 29 April 2024. The decision to build them was made in 2005. It took 19 years to completion.

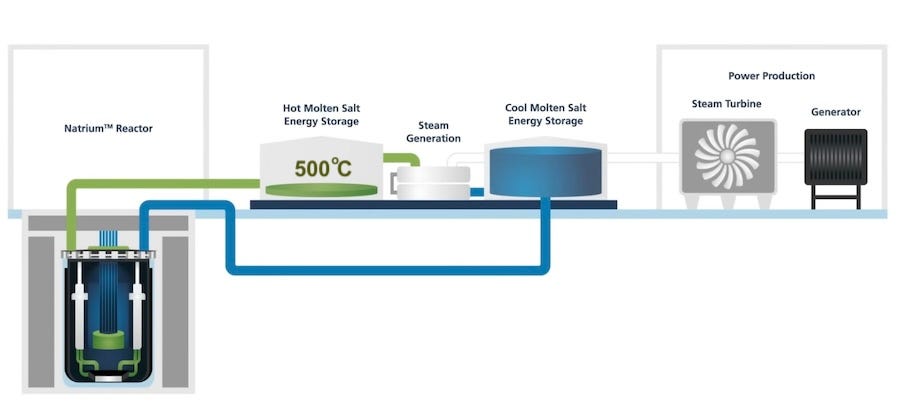

A new technology that is being trialled at the moment in Wyoming is I think far superior to PWR, at least in the deregulated grid paradigm. The so-called Natrium reactor is pushed by a privately-funded company, TerraPower, funded by Bill Gates and friends. A demonstration plant is currently being built in Lincoln County, Wyoming. The nuclear part in this plant will be a sodium fast reactor generating 840 megawatts of heat at 500 °C. The heat will be stored in molten salt. The electricity will be generated by a conventional steam turbo-generator using the stored heat.

If needed, the plant may boost its output to 500 MWe for more than five and a half hours using both the reactor heat and the stored heat. Otherwise, the continuous generation rate is 345 MWe. According to the company literature, the expected plant life is 80 years.

Since the turbogenerator is powered by the heat in the molten salt tank, its output can easily be varied to follow the grid demand. This means it is a fully dispatchable power generator.

Dispatchable Natrium plants will provide stability to the grid even at very high rates of renewable penetration. Are they going to be the best option in terms of cost? I do not know. I do not think so. They are dispatchable but the capacity factors will be low for reasons outlined in the first part of this post. Therefore, they will not be bankable projects. Nevertheless, I think we may see more of them in the interim period with government subsidies until cheap indefinite-term storage technologies become available.

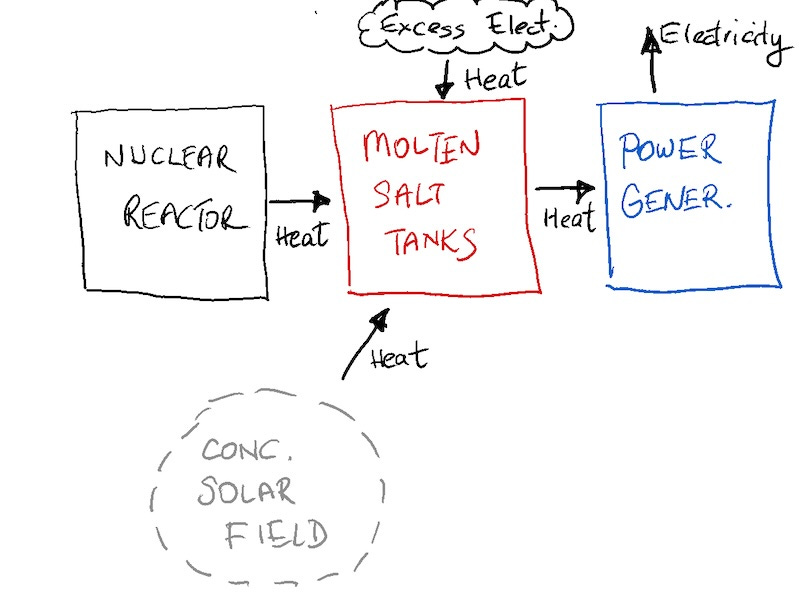

Although this not mentioned in the company literature, a Natrium plant can be extended with interesting options. For example, one can add heat to the molten salt in Figure 4 using a concentrated solar thermal field or even resistive heaters using spilled electricity from the grid. These options of course do not provide for long-term reliability, for which one still needs the nuclear island as I sketched below:

-+-+-+-+

The world's longest UHVDC line in China

Power, 26 Jube 2024, Aaron Larson

A ±1,100-kV DC transmission line starts in Xinjiang and ends in Anhui, passing through Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, and Henan provinces. The 3305-km line has a transmission capacity of 12 GW. The line was commissioned 6 years ago and a recent Power magazine article refers to a presentation to a recent 26th World Energy Congress in Rotterdam, Netherlands in April 2024 by the State Grid Corporation of China (SGCC). The SGCC say it is “the world’s highest voltage level, largest transmission capacity, and farthest transmission distance ultra-high-voltage project.” The NS Energy site says that the construction on the £4.7bn ($5.9bn) transmission project was started in January 2016 and completed in December 2018. Note that this corresponds to $1.8m/km. The NetZero study I referred to above assumed that pipeline hydrogen was cheaper to transmit energy than electricity. I could not find what their transmission line cost assumption was. I doubt that pipeline hydrogen could compete with $1.8m/km transmitting 12 GW.

-+-+-+-+

Carbon Capture Container

A Californian company unveiled the US’s first direct air capture system for mass production: a shipping container-sized machine that can remove 500 tonnes of CO₂ a year.

The IPCC says that at least six billion tonnes of CO2 need to be removed from the air every year to limit average temperature increase to 1.5°C. This would require 12 million of the above containerised CO2 extractors. I do not think this is likely to happen but I included this news here to show how difficult it is to remove CO2 once it is in the atmosphere.

-+-+-+-+

"Tyranny of Distance" no longer an excuse for Australia

Geoffrey Blainey introduced the phrase in his 1966 book "The Tyranny of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australia's History." Blainey used the term to explore and explain how Australia's geographical remoteness has significantly influenced its historical development, economic patterns, and cultural identity.

A recent Substack post by Noah Smith suggests to me that Australia no longer can blame the "Tyranny of Distance" for the social and economic choices we make as nation. Look at the following map:

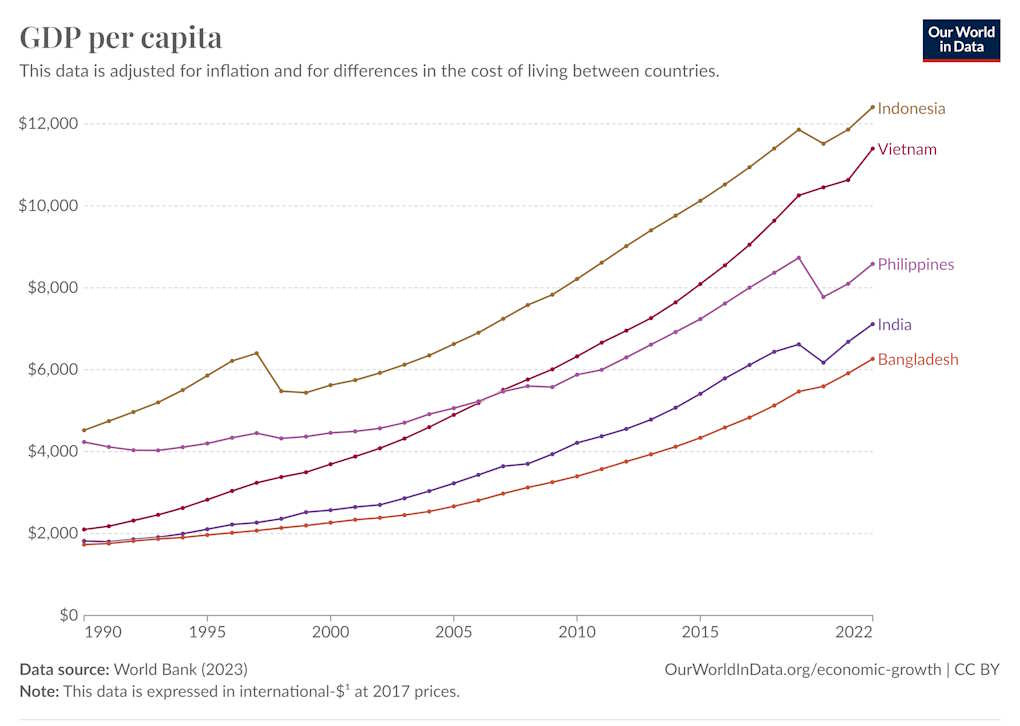

The region as a whole contains a full third of humanity. SASEA has far more people than Africa, East Asia (excluding Southeast Asia), or the entire Western hemisphere. It is notable that even without India, the region would still be more populous than the entire Western hemisphere. The population in the region is still relatively young and the economies are growing. Its largest countries are on a smooth upward growth trajectory, and while none of them are anywhere close to rich yet, all of them have escaped the World Bank’s “low income” category:

Australia has been investing in its relations with India over the last decade. I think we should do the same and more with the other countries in the region. Indonesia is another ascending economy. It also has a large population and unlike India has substantial natural resources. For example, Indonesia produces nearly half of the world’s nickel, a vital raw material for EV battery manufacturing, and in 2020 it banned ore exports, forcing foreign companies to invest in factories in the country.

-+-+-+-+

Pill-sized robot could diagnose cancers

A swallowable robot the size of a pistachio could reduce the need for endoscopies. PillBot, powered by tiny thrusters and controlled by a smartphone app, can send images of the gastrointestinal tract to doctors with minimal patient preparation and no intrusive tubes. Its makers hope the robot, which is beginning clinical trials, will improve stomach cancer diagnoses, many of which are missed because of a shortage of endoscopy staff and facilities. The initial models are manually controlled, but future versions may be autonomous and can even be self-administered by the patient.

You Tube

-+-+-+-+ Last week was the week of the 4th of July, the US Independence Day. I have two YouTube videos both addressing the state of the union.

The first one is from a British historian Niall Ferguson. He compares today’s US to the USSR in 1970s. The USSR had one party with a monopoly on power, the US has a duopoly. There are many other similarities including the gerontocracy at the top, and the despair in the population. I do not agree with all Ferguson says. But I think he is correct on the failure of the US political system to develop solutions and the resultant despondency in the population, which leads to the ascendancy of populists like Trump.

The second video is from a Chinese academic. He draws parallels between the US and the Tang Dynasty. Tang Dynasty ruled from the beginning of the seventh century for three centuries. This period is considered the golden age of China. The video identifies two similarities between the present US and the Tang dynasty:

Privatisation of the treasury and the use of fiat money policies to impoverish the majority of people while a few get very rich; and

Merging of the military with the financial interests.

It is an interesting video. I suggest you watch it at 1.5x speed with captions on.

Diary

-+-+-+-+

Playroom for our Grandchildren

The skip bin was almost full to the brim when it was taken away. It is amazing how much junk accumulates when you are not watching.

We now have a playroom for Eleanor. This was a Meliz project. I was sceptical at first but I am very impressed with the result. Here are some photos:

A closer look at Eleanor’s “kitchen”. She has great fun making “omelettes” for us:

Here are some of her books on the shelves. At the moment, “Spot” series is her favourite:

She has whole families of little people with their little furniture. They are stored in bookcase shelves:

She even has a teepee that she sometimes calls a cave and likes sitting in it guarded by her big giraffe:

My birthday present

-+-+-+-+

When I was a child I had a series of books written by a French author Jean de la Hire: Le Tour du monde de deux enfants. It was translated to Turkish as “İki Çocuğun Devrialemi” and were published in ten separate volumes. It was about two French kids travelling around the world on a motorbike, which was a novelty in 1912 when the book was published. I remember reading all ten volumes many times and being fascinated each time with their adventures in exotic places around the world. Inexplicably, I remembered of this book a few months ago and thought how cool it would be to purchase a copy if it were still in print. I searched in a few usual places but had no luck. I must have mentioned it to Taylan in passing. He remembered and managed to get a copy of the tenth volume for me for my birthday. It is a used book of course but in mint condition. This copy was printed in 2012, which means the book must still have been popular then in Turkey.

Reading the conclusion of the adventures of Janos and Yanik took me back to my childhood years.

Brisbane Haircut

-+-+-+-+

Some readers will remember Eddie, my friend and my barber in Brisbane. You may also remember my haircut in Beşiktaş from my last post. I described Mevlut’s haircut to Eddie. He was not too impressed with the style but he is a professional and I think he tried and delivered what I described. At home, I asked Meliz to take a photo:

Pascal Hagi

-+-+-+-+

Before Pascal ran away (for a month), he was the only lorikeet living with us. Hagi was with Meliz’ mother at that time. In March last year, we got a large aviary built in the yard outside my office and Pascal and Hagi has been living with us since then.

Having Hagi affected Pascal’s psychology. Pascal used to perch on my shoulder when I worked at my desk but this is no longer possible. When Pascal flies onto my shoulder, Hagi comes too and Pascal gets upset because I indulge Hagi and bites me. It is not a love bite. When Pascal bites, it bleeds and it hurts a lot. Incidentally, Hagi never bites. Anyway, I am trying to get them learn to share me. Here is me, trying:

What I read

Last week I read The Glass Bead Game by Herman Hesse. I had read it first over forty years ago but forgot most of it. Hesse won the Nobel prize in 1946 and they say that the Glass Bead Game was a significant influence to the Nobel Committee’s decision.

The story is in an unspecified future century, an era much more stable and peaceful than today. In this stability, there is a country called Castalia and the residents of this country are all highly educated intellectuals. They chase intellectual pursuits which usually have no relevance and no use to the rest of the world, for example, the development of the B-flat minor ascendancy in the choral compositions of the 16th century. One of the pinnacles of the intellectual life in Castalia is the Glass Bead Game. Although the rules of the game are never fully explained in the book, the players appear to compete against each other utilising their mastery of the total knowledge of the world. Similar to the music that has its language with staves and notes, the Game has a language of its own. The entire knowledge of the world can be expressed in this language. In that sense, it reminded me the Large Language Models of today which has the same claim of holding the global knowledge in their models with billions of parameters.

Hesse apparently wrote this book as a joke. This is acknowledged in Thomas Manne’s letter to him where Manne cautions Hesse that most readers probably would not get the joke and would take it seriously.

The story is about Joseph Knecht who enters the Castalian system when he was a young boy and rises through the system to become the Grand Master of the Glass Bead Game. During this process, he becomes aware of how dependent Castalia is to the goodwill of the surrounding nations which how little most Castalians know of. This starts bothering him.

There is not much of a plot. It is more a series of philosophical encounters and awakenings Joseph Knecht meets during his life in Castalia.

Some interesting observations:

Castalia is all males. The wikipedia says that Herman Hesse wrote this book between 1931 and 1943. I do not know the gender balance at the German universities at that time but I suspect they were all male academics. Even then one would expect Hesse to imagine a more enlightened world of the future. Maybe this is a part of a joke that I am missing.

I paraphrase from p 267 a text that could have been the mission statement for a modern university department: ”Attain the utmost command of your subject, and keep your subject vital and flexible by forever recognizing its ties with all other disciplines.” Unfortunately, in most universities that I know of, the latter part of the mission is ignored more often than not. In Hesse’s Castalia, the Glass Bead Game provides this connection between disciplines. Today, the LLMs (or what. they become as they develop) will organically provide the same connectivity.

Hesse did not even try to predict what the world of future will look like in terms of technologies. The most advanced communication technology for example is radio. Even telephone does not get a mention.

It is an interesting book and parts of it I found enjoyable. However, I must confess that I felt a bit flat after this second reading because I was expecting a lot more. Even if I do not remember the contents of the book from the first reading, I remember that I was very impressed with it at that time. This may partly be because it is a “coming of age” book. Joseph Knecht starts as a very idealist youth and we witness how he gets to understand how his idealism is blunted by the reality, how he struggles to avoid becoming a cynic while learning about the compromises one needs to make in life. I guess when I first read the book, like all youth of my age, I also had a partly idealistic view of the world and some of Knecht’s agonies were original and interesting for me. Unfortunately, you lose some of the naivety of the youth when you get old. This may be why some of Knecht’s reflections were no longer as novel and interesting for me as they probably were forty years ago. It is also possible that the 1960-1980 period was a better age for Hesse. I am very interested in comments from younger readers (younger than 40) who read Hesse recently.

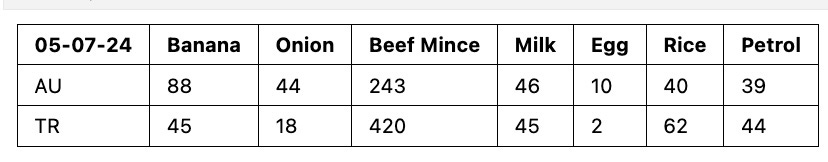

AT index

I am starting a new section where I will be monitoring the Turkish and Australian prices for a basket of items. Turkish prices are obtained from Migros Online, and the Australian prices are from Coles Online. There are the following items in the basket:

Bananas (local product in Turkey, Coles default in Australia)

Brown Onions

Beef Mince (Migros Dana in Turkey, Coles Regular mince in Australia)

Milk (Full cream. Pinar in Turkey, Norco 2-L bottle in Australia)

Eggs (Migros 15-pack in Turkey, Coles free range 12-pack in Australia)

Rice (Migros Baldo pirinc in Turkey, Coles long grain in Australia)

Petrol (Petrol Ofisi for Turkey, RACQ Fair Fuel Finder Sunnybank prices)

Below are the prices in Turkish liras for the items in the basket on 5 July 2024. The conversion rate is 1AUD=22.06TRY

I then calculate an AT (Australia vs Turkey) index as the sum of the ratios (sum(AU/TR)) divided by the number of items in the basket, which is 7.

AT index on 5 July 2024 = 1.67

For non-Australian readers, this is a persistent partnership of Australian Liberal (Liberal Party is the Conservative Party here) and National parties. It is called The Coalition.

As a result of this project, in my fifth month in the country, I had seen more of Queensland outback than most people living in Brisbane could claim.

I find it difficult to accept the latter as a valid argument for upending an entire system. I am sure easier ways could have been found to help company finances.