If interested in AI, check my other page where I write on prospects for LLM tutors.

Please also subscribe to make sure you will not miss future posts. Subscription is free. Your email will not be used for other purposes. You will receive no advertisements.

-+-+-+-+

On 14 December 2025, two shooters at a Hanukkah celebration near Sydney’s Bondi Beach killed 15 civilians and injured dozens.

Police identify the alleged attackers as 50-year-old Sajid Akram and his 24-year-old son, Naveed Akram. The elder Akram was originally from Hyderabad in India and had lived in Australia for decades. He was shot dead by police at the scene. His son, an Australian-born citizen, was critically injured.

Nothing can justify killing of innocents. There is no excuse for the hatred and violence that shattered so many lives. The remaining suspect now faces the Australian legal system.

This tragedy should not be reduced to partisan point-scoring, though in the wake of the attack some political figures and parties have sought to use it to advance their agendas. My purpose here is not to analyse short-term political tactics, but rather to reflect on what current and future Australian governments must do to reduce the likelihood of such violence in the future.

Gun Control

In Australia, firearms licences are issued by state governments, not the Commonwealth. In this case, Sajid Akram held a firearms licence issued by the New South Wales Government and was the registered owner of six rifles, four of which were reportedly used in the Bondi attack. They appear to have been among the most powerful firearms that can be legally owned by civilians

In the aftermath of the attack, both state and federal governments have acknowledged the need to tighten aspects of gun ownership and licensing. Precisely how this should be done is a complex policy question, but several minimum reforms seem reasonable.

First, it should be harder for an ordinary individual to legally own large numbers of firearms. Six rifles is a substantial personal arsenal, and current thresholds deserve closer scrutiny.

Second, information sharing between state firearms registries and federal authorities should be strengthened. Licensing decisions made by states would benefit from fuller access to federal intelligence and security assessments.

Finally, gun ownership should be restricted to Australian citizens. Australia has relatively accessible pathways to citizenship, particularly for long-term residents. Such a requirement would not permanently deprive lawful residents of access to firearms; those who wish to own guns could choose to become citizens. According to media reporting, Sajid Akram had lived in Australia for more than twenty years, during which time he could have applied for citizenship had he chosen to do so.

These measures would not eliminate violence, but they would raise the threshold for access to lethal weapons and reduce the risk that legally owned firearms are used for mass harm.

Control Hate Grooming

By hate grooming, I mean the systematic indoctrination of mostly young people into extreme hatred of people from other religions or ethnic backgrounds. A small but dangerous fraction of those who are hate-groomed go on to translate this hatred into acts of violence, including mass murder.

One uncomfortable question is why organised, systematic hate indoctrination of children appears more frequently in some Muslim communities than in most other migrant or religious groups in Western societies. Bigotry exists across cultures, but it is rare for other communities to embed hostility toward entire religions, ethnicities, or civilisations into structured childhood education. This observation is not an indictment of Muslims as a whole, but of specific practices that deserve scrutiny.

In many Western countries, including Australia, imams and religious instructors are entrusted with educating children in Islamic practices and Quran recitation. Many perform this role responsibly, helping young people maintain a religious identity while integrating into the broader society in which they live. However, a minority appear to see their role very differently — not as educators, but as ideological gatekeepers tasked with hardening young minds against the surrounding culture.

In these cases, the message is not limited to antisemitism. It extends to a broader rejection of Western values — pluralism, secular law, gender equality, freedom of belief — which are portrayed as corrupting forces threatening Islam itself. When such views are instilled in children, the result is not religious education but ideological isolation, with predictable consequences for social cohesion and, in extreme cases, public safety.

Islamic preachers in Australia are typically funded by local communities, charitable organisations, or private donations, with little formal oversight of teaching content outside formal schooling. This creates a legitimate policy question. The issue is not freedom of religion, but whether greater transparency of funding, clearer accountability, and basic safeguards are needed when vulnerable young people are involved in structured ideological instruction.

An interesting contrast can be seen among Turkish Muslim communities in Australia. Many Turkish preachers are funded or overseen by the Turkish state through Diyanet, which imposes formal guidelines, training standards, and disciplinary controls. While this model has its own political limitations, it significantly reduces the risk of unchecked hate indoctrination. Preachers operating under a state authority are constrained by career incentives, institutional oversight, and a version of Islam that is statist rather than revolutionary. This stands in contrast to loosely funded or privately sponsored preaching, where ideology, grievance, and isolation can flourish without accountability.

Fight Anti-Semitism

The previous section makes it clear that hate grooming is not limited to antisemitism. Nevertheless, antisemitic narratives deserve particular attention. Historically, antisemitism has functioned as a cross-cultural carrier of hatred, easily embedded within otherwise unrelated ideological, religious, or political grievances. For that reason, it often becomes a gateway through which broader bigotry is normalised.

It is therefore important that even so-called “minor” antisemitic offences are taken seriously. Acts such as defacing Jewish community centres, schools, or synagogues should not be dismissed as symbolic or harmless. They contribute to an atmosphere of intimidation and exclusion and must be investigated and penalised consistently.

At the same time, it is essential to distinguish antisemitism from legitimate political dissent. Peaceful protest against the actions of the Netanyahu government, or against Israeli government policy more broadly, is not in itself antisemitic. Nor should it be automatically assumed to incite violence against Jewish people.

On the contrary, peaceful protest can serve as a pressure valve. It provides an outlet for anger and moral outrage, allowing grievances to be expressed publicly and lawfully rather than festering in isolation. When conducted within the bounds of the law, such protests can reduce rather than increase the risk of radicalisation.

Early Detection and Prevention

Mass violence of this kind rarely emerges without warning. In most cases, the individuals involved leave signals over time that, in retrospect, point to radicalisation. The difficult question is how a liberal democracy identifies and responds to such signals without eroding civil liberties.

Online platforms have become central to this problem. Ideological grooming increasingly occurs in private or semi-private digital spaces, often fragmented across multiple platforms and encrypted channels. While no system can detect every threat, there is a growing need for better early-warning mechanisms that focus on patterns of escalation rather than isolated statements.

Prevention also depends on information flow within the state itself. Intelligence, immigration records, firearms licensing, and local policing often sit in separate bureaucratic silos. Each may hold fragments of information that appear benign in isolation but become concerning when viewed together. With proper oversight, improved information-sharing may be as effective as expanding surveillance powers.

There is also a role for non-coercive intervention. Schools, community organisations, and local leaders are often the first to notice when young people are becoming socially withdrawn, ideologically rigid, or consumed by grievance narratives. Programs that allow early raising of concerns without criminalising individuals should be strengthened.

None of this offers certainty. No intelligence system can guarantee prevention, and false positives carry real costs. A serious prevention strategy can only aim to reduce risk not eliminate it.

Conclusion

The Bondi attack did not arise from a single failure. It emerged where access to lethal weapons, ideological grooming, antisemitic narratives, and gaps in early detection intersected. Addressing any one of these in isolation risks missing the broader lesson.

Gun control matters because it governs access to irreversible means. Hate grooming matters because it shapes motive long before violence occurs. Antisemitism matters because it remains a uniquely portable and potent form of hatred. Intelligence and prevention matter because, without early intervention, these forces can converge unnoticed until it is too late.

No single policy can guarantee prevention, and a liberal democracy should not police belief. But it can raise thresholds, improve oversight, and intervene earlier and more carefully when patterns of risk begin to form. Doing so is not a retreat from openness, but a condition for preserving it.

Reducing the likelihood of future tragedies will not come from slogans or partisan point-scoring, but from sustained, sober attention to how violence is enabled; so that we can act earlier, and more wisely, at every point where it can still be stopped.

-+-+-+-+

Short Takes

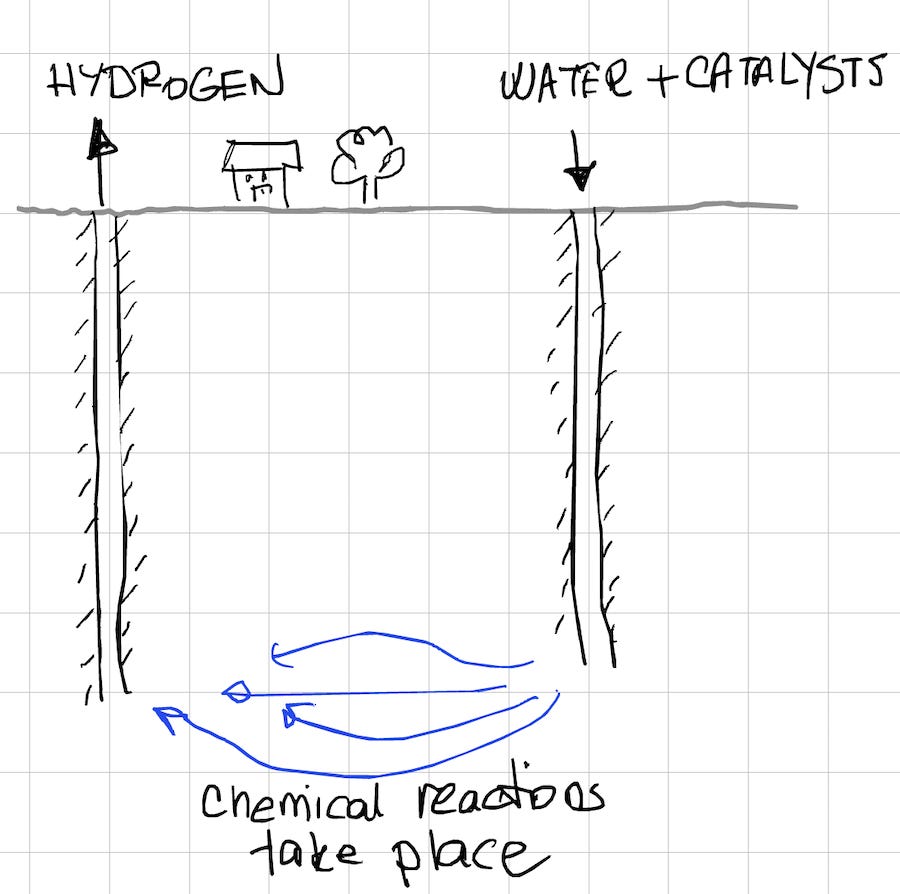

Hydrogen from underground chemical engineering?

Vema Hydrogen claims it can generate hydrogen underground by accelerating naturally occurring chemical reactions, injecting water—possibly non-potable—along with catalysts into suitable rock formations. While the company’s literature is light on technical detail, the basic idea appears to be as follows: water is injected through one well, reacts with the surrounding rock as it migrates through the formation, generates hydrogen, and the gas is recovered via a second well.

Vema has recently signed a 10-year agreement to supply more than 36,000 metric tonnes of hydrogen per year for powering data centres.

I hope they succeed, but this is a difficult call. Anyone familiar with Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) knows how hard it is to push water from one well to another—the impermeability of rock is unforgiving. Here, the challenge is even greater: you are not just moving fluid, but trying to generate and reliably extract a gas. That is a tall order.

-+-+-+-+

Comparing Istanbul and Brisbane prices - AT index

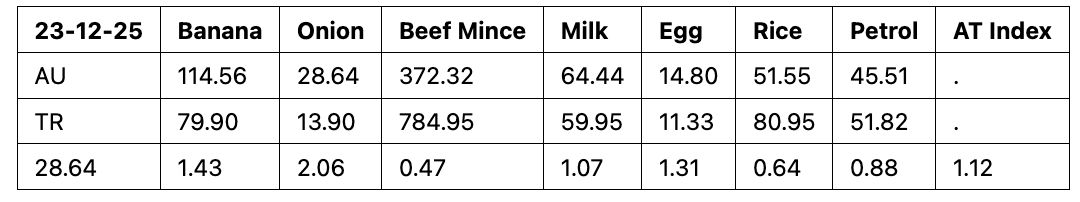

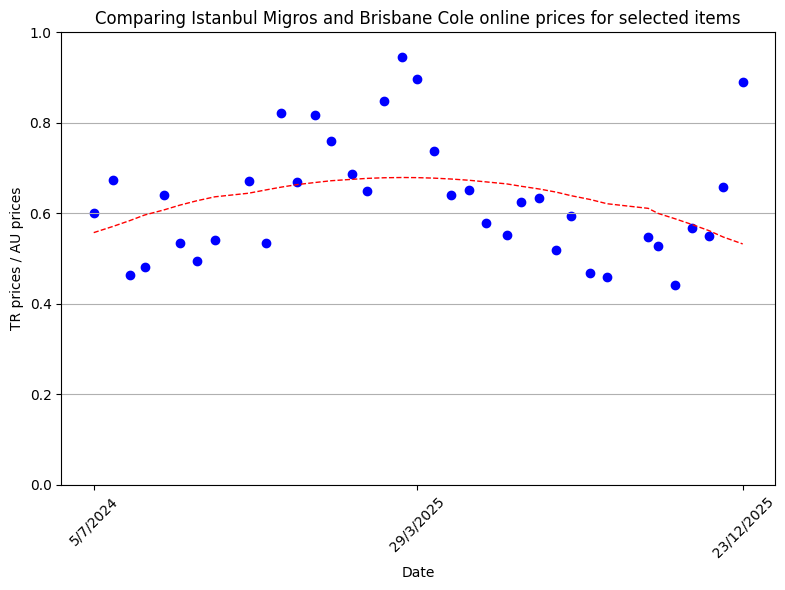

Based on my basket of goods, I compare Turkish and Australian prices. Both Coles (AU) and Migros (TR) prices are expressed in Turkish liras in the following tables. I converted Coles prices to Turkish liras at the exchange rate of 1AUD=28.64TRY.

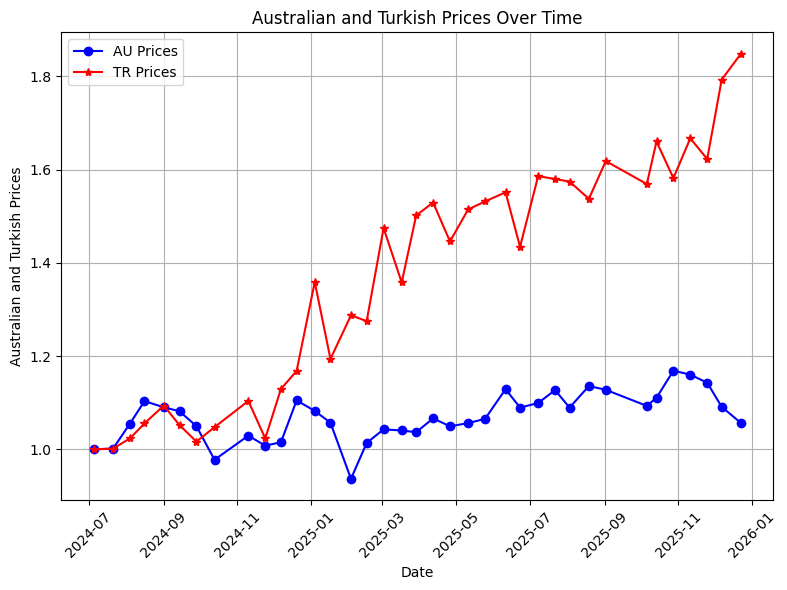

I started this section on 5 July 2024. The Turkish prices initially rose fast. Since February 2025, the Turkish prices had been getting increasingly lower compared to the Australian prices. The trend seems to have been reversing for the last several weeks with the Turkish prices rising again compared to the Australian prices.

Some items, e.g. beef mince and rice, have consistently been more expensive in Istanbul. Raw data can be downloaded from my github page.

The following chart shows the variation of the total cost for the basket in each country separately taking 5 July 2024 as the base.

Wages

The Australian minimum wage was increased to almost $25/h on 3 June 2025. This corresponds to A$4000/month for a 160-hour month. The Australian workers being paid the minimum wage are about 2.6 million or about 18% of the total Australian work force.

The minimum wage in Turkey is 26,000 TRY/month. At the current exchange rate this corresponds to A$1018/month.

The code to create the above tables and the charts is in my github repository and can be downloaded if you are interested

Statistics

The current count is 438 subscribers; 557 followers.

I thank you all for your support. Please continue your shares and mentions.